Part One: Enter Autolycus Singing

Part one provides a very quick recap up to the point that Autolycus, the focus of the remainder of this article, makes his entrance. What follows are descriptions of Autolycus and his parallels with Bob Dylan; a consideration of the peddler figure in The Winter’s Tale and Visions of Johanna and an examination of the credo “to live outside the law you must be honest”.

A quick summary of The Winter’s Tale

King Leontes of Sicilia wrongly suspects his wife Hermione of having an affair with his friend King Polixenes. Consumed by delusional jealousy, Leontes loses contact with reality. He imprisons Hermione, orders their newborn daughter (Perdita) to be abandoned and left for dead. During this traumatic time, his young son dies. The Oracle pronounces Hermione innocent, but by the time Leontes believes it, she has collapsed and is presumed dead. Wracked with guilt, Leontes vows lifelong penance. Perdita is found and raised by shepherds in Bohemia. Sixteen years pass, (yes sixteen years and there are desperate men, desperate women and good shepherds), a passage of time resonant in myth and numerology.[i] Perdita, now on the cusp of adulthood, stands at the symbolic threshold between girlhood and womanhood, innocence and maturity, a living symbol of the theme of lost and recovered identity.

When Act IV begins, the world of the play shifts from tragedy to pastoral comedy when, in scene three, Autolycus, a comic rogue and peddler of wares, takes to the stage, singing as he enters. His arrival marks a tonal transformation, as the play enters its comedic and restorative phase. Autolycus roams the countryside tricking people out of their money. As his antics become entangled with the romantic subplot between the now-grown Perdita and Florizel (the son of Polixenes), so his relevance and bearing on Shakespeare’s profound themes develop apace.

It is noteworthy that the trickster figure of Autolycus enters singing. He ushers in the play’s new tone and setting, that of comic-romantic pastoral, in song.

Scene 3

Enter Autolycus singing.

AUTOLYCUS

When daffodils begin to peer,

With heigh, the doxy over the dale,

Why, then comes in the sweet o’ the year,

For the red blood reigns in the winter’s pale.

His first appearance, is framed in music as the balladmonger roams the countryside. You can listen to here:

In between the songs, which bracket this first appearance, Autolycus first deceives, then robs, the Shepherd’s son.

Autolycus, meaning “very wolf-like”, was also the name of a Greek demigod, the son of Hermes (Mercury in Roman times) and the grandfather to the legendary Odysseus (Ulysses.) Hermes was the god of trade, thieves, and trickery as well as being the swift messenger from the Olympian Gods, and Shakespeare’s Autolycus is cut from the same cloth. The balladmonger and con-man immediately introduces himself by announcing his lineage: “My father named me Autolycus, who, being, as I am, littered under Mercury, was likewise a snapper-up of unconsidered trifles.” That last phrase is a lovely insight into his character. A disarming description, deflecting the plain truth of one prime part of his roguery, theft.

“If I was a master thief / Perhaps I’d rob them” sings Dylan in “Positively 4th Street”; well, Shakespeare’s Autolycus is indeed a master thief and like the Autolycus of classical myth, he has inherited many other skills from his father Hermes, namely: trickery, disguise, a chameleon-like shape shifting ability. Additionally, and very pertinently for us, he was also blessed with exceptional skill on the guitar-like lyre and had a mesmeric power as a singer of songs. So, like Dylan, Autolycus reached his audience through the popular appeal of ballads and singing. Like Dylan, too, he is a master of masks, and, like Dylan again, he is a teller of tall tales and fantastic stories, especially regarding his own background and identity.

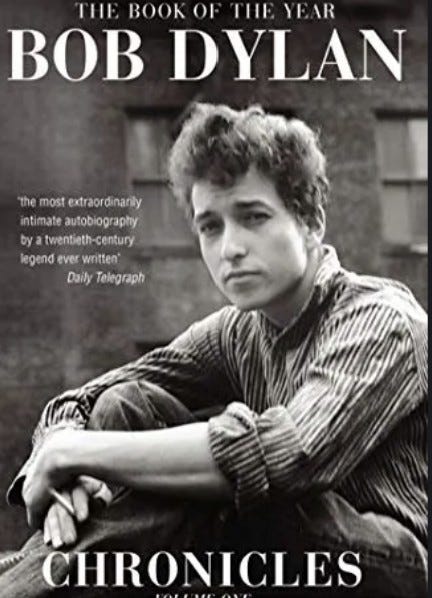

Another similarity to Dylan comes in speed. The servant announcing Autolycus’s arrival tells us that; “He sings several tunes faster than you’ll tell money. He utters them as he had eaten ballads and all men’s ears grew to his tunes.” Dylan tells us in Chronicles that “I did everything fast. Thought fast, ate fast, talked fast and walked fast. I even sang my songs fast”. Both singers, then, are associated with a rapid-fire delivery of songs that highlighted the ubiquity and captivating nature of ballads. The servant goes on to claim of Autolycus that, in a further parallel to Dylan, “He hath songs for man or woman, of all sizes.”

A final resemblance between the invented character of Autolycus and, you could say, the invented character of Bob Dylan, is the concept of living honestly outside the law and their ballads featuring the likes of the Robin Hood and Pretty Boy Floyd ballad trope of outlaws who perform just and kind acts.

The archetype of the trickster thief has been extensively written about in Dylan studies, sparked in part by those frequently discussed themes of borrowing, appropriation, and imitatio, which involve digesting and transforming source material.[ii] Partly also by Dylan’s self-identification with the thief in his writing, as in the sublime “Tears of Rage” when he pleadingly asks, “Why must I always be the thief”. Autolycus embodies Dylan’s famous line, “to live outside the law you must be honest.” He believes the time for such a philosophy has arrived: “I see this is the time that the unjust man doth thrive. ” In Dylan & Shakespeare: In The True Performing Of It, I wrote of how: “The poet Allen Ginsberg, while teaching a course on Shakespeare’s The Tempest, told his class that, in a telephone call with Dylan in the Sixties, Bob had remarked that “to live outside the law you must be honest” was the favourite of his own lines. Dylan had described it as his “supreme Shakespeare shot”.

Ginsberg linked the paradox in the Dylan line with Shakespeare’s characteristic mode of expression. He brought it up while discussing Shakespeare’s “constructions of paradoxical phrasing” and the “polarity of opposites”, which Ginsberg describes as an “automatic poetry” of “yoking opposites” together but which have “got to make sense, though”. This prompted Ginsberg to quote the famous Dylan line and recount the telephone call. Ginsberg then said of Dylan’s line: “The contradiction is so apt, so perfect, so simple – it’s the simplicity that does it.””[iii]

Autolycus is introduced as a vagrant, a former servant now heartily embracing a life of duplicity and petty theft alongside his ballad-selling. His roguish nature aligns with the potential for deception inherent in the ballad trade, where, in tabloid fashion, sensationalist sheets often eschewed any pretence at accuracy. At the same time, however, we recall that in the traditional ballads, the impossible-sounding wonders would speak to a deeper truth, as in Dylan’s “all those songs about roses growing out of people's brains and lovers who are really geese and swans that turn into angels”.[iv]

Autolycus, it is universally agreed, is a charming rogue. Every production has to decide how much emphasis to place on each half of that description. However that balance is weighted, he remains an unrepentant thief and liar. However, against his “better” instincts (i.e. those of knavery and deceit) Autolycus ends up bringing about the play’s miraculous ending, one of the many paradoxes the last two scenes so keenly explore, often through this beguiling character.

Just as Shakespeare brings a peddler into his The Winter’s Tale, so, too, does Dylan bring one into his “Visions of Johanna”: The peddler now speaks to the countess who’s pretending to care for him. Stephen Scobie[v], when writing on the song, remarks that: ““Peddler” suggests a vagabond, someone out on the road with something to sell…”. This reminds us of other Dylan songs from the time, such as: The vagabond who’s rapping at your door from “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue” and Miss Lonely in “Like A Rolling Stone” who once “threw the bums a dime” when in her “prime”.

All of which brings us back, as does Autolycus’s vagrancy, to the history of minstrels and travelling players -and Dylan’s early days and the wandering musicians he sought to emulate - as documented in part 4 of this series, “Voices of the People. It is worth noting, in passing, that the social contrast in the characters in Dylan’s songs, especially ‘peddler/countess’, is a key component of the latter part of Shakespeare’s play where Autolycus dons the disguise of a nobleman.

On Blonde on Blonde’s, “Visions of Johanna”, then, we hear of the peddler who speaks and of the fiddler who now “steps to the road”.

The peddler now speaks to the countess who’s pretending to care for him

And Madonna, she still has not showed

We see this empty cage now corrode

Where her cape of the stage once had flowed

The fiddler, he now steps to the road

He writes ev’rything’s been returned which was owed

On the back of the fish truck that loads

While my conscience explodes

It was not always this way; in two earlier versions from 1965, boasting alternate titles, the characters fiddler/peddler characters were flipped around from the Blonde on Blonde incarnation. You can hear the studio “Seems Like A Freeze-Out” here, with the following lyrics:

The peddler now speaks to the countess who pretends that she cares for him

And Madonna, she still has not showed

We see this empty cage now corrode

Where her cape of the stage once had flowed

The fiddler, he now steps to the road

Knowing everything’s gone which was owed

He examines the nightingale’s code

Still left on the fish truck that loads

My conscience explodes

Additionally, the first known live recording, “Alcatraz to the 9th Power Revisited”, Dec 5th 1965, has:

The fiddler now speaks to the countess who’s pretending to care for him

And Madonna, she still has not showed

We see this empty cage now corrode

Where her cape of the stage once had flowed

The peddler, he now steps to the road

Everything’s been returned which was owed

He examines the nightingale’s code

Still left on the fish truck that loads

My conscience explodes

The extra line these share, regarding “nightingale’s code” has been the subject of much analysis and debate, but my concern here is with who speaks to the countess and who steps to the road, the latter being what old minstrels, travelling players and balladmongers did, just as Woody, Cisco, Lead Belly and company did, and a certain touring musician does to this day, even at the age of 84.

Does it matter which way round the peddler and the fiddler appear? Not really, they both relate to itinerant folk musicians (fiddles being very portable, peddlers hawking ballads) and they both have dodgy connotations: “peddling lies” and “fiddling the figures”. Thomas Nashe, you may recall in a tirade against balladeers used “fiddler” as one of his string of insults: "stitcher, weaver, spendthrift or fiddler [who] hath shuffled or slubber’d up a few ragged rimes."

The very word peddler is etymologically confusing and contentious. What was long assumed to be the later spelling, “pedlar”, was possibly an earlier spelling, too. In Scots, it’s clearly derived from from “pedalare” with the emphasis “ped”, from the Latin for foot and via many middle-English derivatives. A peddler (traditional Scots spelling, modern American spelling) travels by foot, selling all manner of trinkets along with broadside ballads. So, I would, given the choice, prefer it to be him and not the fiddler who was “steps to the road”. My own slight preference in the matter is, however, of no consequence. As Stephen Scobie goes on to suggest, the terms peddler/fiddler refer to the same person, whom he interprets as Dylan himself.

A foreshadow of Dylan’s peddler/countess contrast is seen with Autolycus representing what was seen as a lower form of popular culture. The educated elite tended to relate what they saw as the ballad's literary inferiority directly to the vagabond status of the ballad seller and ballad writer. As previously noted, there was a law passed in 1572 that made a clear distinction between official acting companies and ballad singers and this instigated a hierarchy of players where ballad sellers and "wandering minstrels" were placed lower than established theatre groups and professional musicians with noble patronage.

Shakespeare is then, undoubtedly poking some fun at the balladmongers’ expense for his theatre audiences; but at the same time he acknowledges, by the play’s conclusion, the close affinities of the two mass entertainments of the age, springing from oral, folk roots and blossoming in this new time of print.

Autolycus is primarily a balladmonger though he has other strings to his bow; Dylan is a ballad monger to a significant extent, though he has many other areas of artistic expression; Shakespeare, I have hopefully made clear, was a balladmonger to a larger extent than is commonly assumed (small though it be amidst his larger enterprises.) If he could not find a ballad to suit the needs of his play, he would simply write one himself, as is presumed to be the case in this very play. No problem: he was Shakespeare, after all.

Part Two: To Live Outside the Law You Must Be Honest

Autolycus’s second appearance shows us a balladmonger at work on Shakespeare’s stage. Through him, Shakespeare raises questions over the relationships between print and truth, art and artifice, legitimacy and illegitimacy. In linking to the final act it also questions wonder and belief, language and reality, knowledge and storytelling.

You can listen to it here:

Autolycus’s second appearance presents us, this time in a rural setting, the kind of exchange that Ophelia mimics in Hamlet, as described here. The scene where Autolycus sings (and sells) "Get you Hence for I must Go" shows him teaching the ballad tune to the shepherd’s son and his girlfriend, Mopsa. The actor playing Autolycus is simultaneously teaching the theatre audience the tune, too, presumably hoping they too will want to buy it. One suspects it would not be difficult for them to locate a copy when in the environs of the Globe or Blackfriars’ theatres. As the previous posting in this series explored, such exploitation of customers for both the theatre and the printed ballad were not uncommon.

Due to his earlier theft, Autolycus is disguised. He is, in fact, an actor playing a balladmonger disguised as a balladmonger. His ballad mongering is soon in action:

SHEPHERD’S SON What hast here? Ballads?

MOPSA Pray now, buy some. I love a ballad in print alife, for then we are sure they are true.

AUTOLYCUS Here’s one to a very doleful tune, how a usurer’s wife was brought to bed of twenty moneybags at a burden, and how she longed to eat adders’ heads and toads carbonadoed.

MOPSA Is it true, think you?

AUTOLYCUS Very true, and but a month old.

DORCAS Bless me from marrying a usurer!

AUTOLYCUS Here’s the midwife’s name to ’t, one Mistress Taleporter, and five or six honest wives that were present. Why should I carry lies abroad?

The ballads Autolycus offers for sale are clearly parodies of the sensational and often unbelievable content found in contemporary street ballads. However, Shakespeare – like Dylan after him (remembering: “all those songs about roses growing out of people's brains and lovers who are really geese and swans that turn into angels”) – is also well aware of the wondrous nature of authentic, traditional ballads and their store of unbelievable action and figures whose magic holds a deeper truth. Shakespeare play will then turn this into a profound examination of nature and art, language and reality.

For now, we listen to Autolycus reel in his country prey with tales of "how a usurer's wife was brought to bed of twenty money-bags at a burthen and how she longed to eat adders' heads and toads carbonadoed". He is soon upping the ante in his tall tale telling:

AUTOLYCUS Here’s another ballad, of a fish that appeared upon the coast on Wednesday the fourscore of April, forty thousand fathom above water, and sung this ballad against the hard hearts of maids. It was thought she was a woman, and was turned into a cold fish for she would not exchange flesh with one that loved her. The ballad is very pitiful, and as true.

DORCAS Is it true too, think you?

AUTOLYCUS Five justices’ hands at it, and witnesses more than my pack will hold.

Notice Autolycus’s various claims to factual truth through purportedly real (and pointed) names, "Mistress Taleporter", plus the assertion that his narrative is, "but a month old" (and so no time to grow “arms and legs”) and backed by the authority of "Five justices' hands at it, and witnesses more than my pack will hold". Shakespeare is satirising the gullibility of Autolycus’s audience on one level, but the theatre audience laughing at their naivety will soon find themselves witnessing another scene where belief in the seemingly unbelievable plays a central role The reach of print ballads across the nation through society was clearly of interest to Shakespeare, as we have seen throughout this series, and nowhere more so than here in The Winter’s Tale. Shakespeare, as you would expect, has a heightened perception of popular faith in the printed word, however incredible its claims may appear.

The perception of printed ballads as inherently "true,", as expressed by Mopsa: “I love a ballat in print, a-life, for then we are sure they are true” may sound silly to us, especially given the examples we hear. However, remembering that broadsheets were not just for ballads, but also trafficked in gossip, slander, news of all shades of authenticity and falsehood. it is clear that they were the popular media of their time: that is, the sensationalist press, the X, the TikTok of its day. Consequently, it is not so very dissimilar to being told nowadays: “I read it in the ’paper, it must be true”, or even less reliably, but still held by many to be factual, “it is doing the rounds on WhatsApp” or the dreaded “I saw it on Facebook” and so forth.

It may be risible, yes, but Shakespeare is having fun with an early version of the same phenomenon. And, just as today’s laughter at “fake news” is often tinged with unease, so too is the audience’s amusement here shadowed by a contemporary anxiety over the social consequences of print’s rapid proliferation.

These anxieties were well-founded. Print was escaping the control of church and state authorities; it was no longer confined to official pamphlets or authorised propaganda. As Aaron Kitch[vi] and other commentators have illuminated, The Winter’s Tale’s themes of legitimacy and bastardry are also entangled with the idea of print culture. Autolycus’s trade in printed ballads, which mix truth with fiction, reflects the play’s anxieties about uncontrolled reproduction, whether of people, stories, or meaning. Just as Leontes suspects his wife’s fidelity and questions the paternity of Perdita, printed texts raise similar concerns about authorship, authenticity, and the boundaries of truth Furthermore, Autolycus’s ballad description featuring a woman birthing money-bags conflates unnatural reproduction with the artificial generativity of print and finance, illustrating a world where forms of “copying” proliferate without clear origin or legitimacy.

This metaphor of print as a standard for both biological and textual reproduction occurs throughout the play. Paulina defends Perdita's legitimacy in this language: “copy”, "mould," and "print "as if the child were a printed text whose source could be verified as though it would be “true” if it could be seen printed on a newspaper “sheet”. Leontes’s craves the “purity and whiteness of my sheets" (paper/bedclothes) - reminding us of Othello in chapter 2 of this series - before they are sullied by ink, and posits paternity as something as clear and unambiguous as a printed page. Yet, as Kitch demonstrates, the very act of printing, like procreation, resists such control. There is even a ‘bastard typeface’, batârde, with its cursive, gothic appearance which was seen as a kind of illegitimate print. In this way, the play reveals a deep-seated cultural unease with both biological and textual reproduction where every child, like every printed word, bears the risk of being a copy without a legitimate origin. This lack of proven legitimacy was a dagger in the heart of a political, religious and financial societal system so utterly predicated on the shaky premise of patrilineal rights.

While concern over widely held belief in the printed word is highlighted, Shakespeare also acknowledges a positive aspect of such belief, both in his own work and that of the balladeer, which he explores fully in the play’s final act.

Furthermore, Autolycus' ballads existed in a space between the printed word and oral tradition. While they were printed and sold, their life extended through being sung, retold, and changed in performance. Autolycus embodies the tension between the permanence of print and the adaptability of oral storytelling, a point central to all my writings on Dylan and Shakespeare. It is only natural that Shakespeare would display such a nuanced and perceptive understanding of the ballad world. As Tiffany Stern puts it:

“Ballads may have seemed, then, a model for what plays could be: they sold excellently both as performance and print, without letting the one ever fully give way to the other.”[vii]

In considering this, and other parallels between balladry and theatre craft, Shakespeare is inspired to answer, or, rather, transcend the questions earlier posed regarding fact and fiction, reality and fantasy, belief in the seemingly impossible .

The final act: It is required / You do awake your faith.

The climactic action centres on a seemingly miraculous reanimation of a statue of the presumed long-dead queen, Hermione. As such, it is, unsurprisingly, presented in terms of wonder and in which Shakespeare takes extraordinary care in framing theories and questions regarding faith, disbelief, art, and reality.

Furthermore, the parallels with the preceding act are made crystal clear. The story is reported by a “second gentleman” explicitly making the link to Autolycus and his main trade: “The oracle is fulfilled: the King’s daughter is found! Such a deal of wonder is broken out within this hour that ballad makers cannot be able to express it” (Act V scene ii). Just as Autolycus peddles unbelievable tales to an audience eager to accept them as true, so Paulina composes an incredible spectacle that her courtly audience is just as keen to embrace. The audience in the theatre suddenly find themselves in the same place as both Autolycus’s and Paulina’s onstage ones and it is no coincidence that it is music which reawakens Hermione to life.

“Tales are false” is the repeated message: Mistress Tale-porter is by her own naming, a carrier of them, Autolycus, in a life dedicated to falsehood, is a peddler of fanciful tales. Shakespeare, too, is a tale teller (as is Dylan, of course). On first viewing, the theatre audience holds its breath and feels the call to “awaken faith” just as Paulina’s onstage audience so. Even when seeing it later, if you witness even a competent, far less a high-quality, production of The Winter’s Tale, the sense of wonder is still palpable as the extraordinary scene unfolds, even when you know the background narrative. Perdita’s instructions to the onstage audience to awaken their faith in the story she is presenting, apply to all audiences of all art and entertainment.

So, Hermione is not resurrected but is simply a human who has aged, as we all do, and has been there all the time. In the context of the play, that truth is itself a wonder, a natural wonder, yes, though a natural wonder rendered by Shakespeare’s art. Hermione, after all, is a character created by Shakespeare and portrayed then by a boy actor. Is it a triumph of nature, or a triumph of art over nature? And is this Shakespeare demonstrating that his art outdoes even the balladmongers grandest wonders, that he can present that which “ballad makers cannot”? Questions beget more questions; one of Shakespeare’s and Dylan’s greatest gifts to us is that they prompt us to ask the important ones.

The fear of “fake news” is brought back into the conversation, by the “third gentleman’s” rejoinder to the second’s above: “This news which is called true is so like an old tale that the verity of it is in strong suspicion.” This line is characteristic of a play that consciously, and repeatedly, calls attention to its inherently unbelievable status; and it does so by linking itself to ballads and "old tales" which as it continually points out are incredible and cannot be accepted as “true”. Yet, the story's conclusion of Hermione's wondrous transformation from a statue, requires just such a belief in the unbelievable from its courtly audience as Autolycus’s grotesque births and transformations do of his rural dupes. Shakespeare, unlike a ballad writer, can present his miraculous transformation through a visually demonstrable reality (albeit a theatrical one), rather than a purely verbal story, thus trumping the unreliable popular ballads he had staged in the preceding act.

Due to the transforming power of performance art, the impossible, incredible, and unbelievable ultimately reveal a deeper truth. As Dylan puts it, in Chronicles, “it was so real…it was life magnified”:

“I had already landed in a parallel universe, anyway, with more archaic principles and values; one where actions and virtues were old style and judgmental things came falling out on their heads. A culture with outlaw women, super thugs, demon lovers and gospel truths . . . streets and valleys, rich peaty swamps, with landowners and oilmen, Stagger Lees, Pretty Pollys and John Henrys-an invisible world that towered overhead with walls of gleaming corridors. It was all there and it was clear-ideal and God-fearing-but you had to go find it. It didn’t come served on a paper plate. Folk music was a reality of a more brilliant dimension. It exceeded all human understanding, and if it called out to you, you could disappear and be sucked into it. I felt right at home in this mythical realm made up not with individuals so much as archetypes, vividly drawn archetypes of humanity, metaphysical in shape, each rugged soul filled with natural knowing and inner wisdom. Each demanding a degree of respect. I could believe in the full spectrum of it and sing about it. It was so real, so more true to life than life itself. It was life magnified. ”[viii]

The climax to the play is a daring thing in the climate of the times. The word “magic” is never far away and it feeds into Catholic/Protestant divisions of belief and bluntly put, belief in such was against the law and such miracles were regarded as belonging to the older, Catholic faith.[ix]

Paulina defends herself before her “show” begins: .

But then you’ll think—

Which I protest against—I am assisted

By wicked powers.

And continues:

It is required

You do awake your faith. Then all stand still—

Or those that think it is unlawful business

I am about, let them depart.

(Act V Scene iii)

Shakespeare here protects himself by insisting that the magic invoked is “lawful” and then we discover the “magic” itself not “real” in a literal sense, but instead only a clever deception. The magic remains very real in a figurative sense and that wonder is felt throughout the audience, The play, as a whole, conveys a love of the marvel and magic of old winters’ tales to tell or sing by the fireside. It is in the wonders of these non-factual narratives, songs and performances that the profoundest truths are to be found. As a consequence, just as the country yokels give themselves up to the extravagant claims of Autolycus’s ballads, so the court in the final scene chooses to believe in the "magic" of Hermione's reanimation. As Leontes, brought at last to full understanding of the human condition, exclaims;

If this be magic, let it be an art

Lawful as eating.

(Act V Scene iii)

Substack Outro:

This brings me almost to the end, for now, of my further exploration of ballads in the works of Shakespeare and parallels that can be drawn with Dylan. There is still a roundup of odds and ends and a description of what was to have been the next chapter (and why it is not appearing here) to go, and a hint of what remains left for potential future expansion. Thanks, to all of who have done so, for sticking with it thus far. For now, I give the last words here to Louis MacNeice’s, from his description of that “loveable rogue”, Autolycus:

“ … — Watch your pockets when

That rogue comes round the corner, he can slit

Purse-strings as quickly as his maker's pen

Will try your heartstrings in the name of mirth.

Brooches, pomanders, broadsheets and what-have-you,

Who hawk such entertainment but rook your client

And leave him brooding, why should we forgive you

Did we not know that, though more self-reliant

Than we, you too were born and grew up in a fix?”

©Andrew Muir, 2025 With thanks to Rowland Wymer.

Acknowledgements and Bibliography

All quotations from the play are from: The Winter’s Tale Edited by Barbara A. Mowat and Paul Werstine with Michael Poston and Rebecca Niles. Folger Shakespeare Library: https://shakespeare.folger.edu/shakespeares-works/the-winters-tale/

Play listening excerpts are from: Shakespeare: The Complete Works: Argo Classics Audible Audiobook performed by the Marlowe Dramatic Society and Professional Players. Full details and purchase, here: Shakespeare: The Complete Works: Argo Classics (Audio Download): William Shakespeare, Ian McKellen, Derek Jacobi, Diana Rigg, Roy Dotrice, Prunella Scales, Timothy West, full cast, Argo Classics: Amazon.co.uk: Audible Books & Originals

Bibliography:

Brown, Mary Ellen: “Placed, Replaced, or Misplaced?: The Ballads' Progress”, Ballads and Songs in the Eighteenth Century (SUMMER/FALL 2006), Vol. 47, No. 2/3pp. 115-129

Cox, Lee Sheridan: “The Role of Autolycus in The Winter's Tale” Studies in English Literature, 1500-1900 , Spring, 1969, Vol. 9, No. 2, Elizabethan and Jacobean Drama (Spring, 1969), pp. 283-301

Kitch, Aaron: Bastards and Broadsides in "The Winter's Tale Renaissance Drama , 1999-2001, New Series, Vol. 30, Institutions of the Text (1999-2001), pp. 43-71

Pafford, J. H. P: Music, and the Songs in The Winter's Tale in Shakespeare Quarterly, Vol. 10, No. 2 (Spring, 1959), pp. 161-175 Oxford University Press

Stern, Tiffany: “Shakespeare, The Balladmonger?” Bloomsbury Collections - Rethinking Theatrical Documents in Shakespeare’s England.

Stern, Tiffany F. W. Bateson Memorial Lecture Ballads and Product Placement in the Time of Shakespeare cgac023.pdf

[i] “16 years” is used also in Shakespeare’s first of his four late romances, Pericles, where the lost royal daughter there, Marina, is also is found again at that age, like Perdita, neither child nor fully adult; at what was seen as an acceptable age for royal women to be courted or married. Perdita, as a "princess" raised among shepherds, fits this mould, see also Miranda in The Tempest, in addition to Marina in Pericles.

Also, in numerology, it is significant in that it is 4 x 4, with 4 representing stability and reliability, but here is not the place to pursue such roads, though it is worth noting that both Shakespeare and Dylan show interest in and knowledge of this field in their respective works.

[ii] See Muir, Andrew Dylan & Shakespeare: In The True Performing Of It…..for a detailed investigation into all these areas.

[iii] Muir, Andrew, Ibid .and http://www.openculture.com/2014/03/hear-allen-ginsbergs-short-free-course-on-shakespeares-play-the-tempest-1980.html Accessed March 28, 2018

[iv] Dylan, Bob: interviewed by Nat Hentoff for Playboy February 1966.

[v] Scobie, Stephen: Alias Bob Dylan Revisited Red Deer press, US, 200 (pp270)

[vi] Kitch, Aaron: Bastards and Broadsides in "The Winter's Tale, Renaissance Drama , 1999-2001, New Series, Vol. 30, Institutions of the Text (1999-2001), pp. 43-71

[vii] “Shakespeare, The Balladmonger?” Bloomsbury Collections - Rethinking Theatrical Documents in Shakespeare’s England.

[viii] Dylan, Bob Chronicles Simon & Schuster, UK, 2005

[ix] This is a vast and complex topic. As such, generalisations are insufficient to give a true picture here. It is worth remembering, though, that belief in magic was fairly widespread even as scientific advances heralded a more modern mindset. The King himself, head of the Protestant Church, was intensely interested in witchcraft, so ambiguities and uncertainties were commonplace. Plus, of course, many clung to the older Catholic beliefs, though it was wise to be circumspect about this, and would have taken to a miraculous resurrection in a private chapel quite readily, but that made it all the more imperative that Shakespeare trod carefully in the scene.

Fantastic piece, Andy! The parallels you draw between Dylan and Autolycus are fully persuasive. You also take me down other intriguing paths I hadn't considered in Winter's Tale. I particularly liked the connections between concerns over legitimacy/bastardy and anxieties over print culture. You had me humming "Someone's got it in for me / They're planting stories in the press" in that section. And my goodness, Andy, what a cliffhanger in the outro! I'm more eager than ever to see where you're going next with this project. Onward!

A wonderful analysis. I will be thinking of Bob (and your words) when I attend a production of Winter's Tale a few weeks from now.