Substack Intro

In the last article in this series, we examined the distinct, albeit overlapping, traditions of "street ballads" (often akin to "protest songs") and traditional ballads. Dylan emerged onto the Greenwich Village folk scene and rapidly established himself as a master of both. It appears that, due to his subsequent achievements in the mid-1960s, this earlier period of the 1960s has been increasingly downplayed. For instance, The Times They Are a-Changin' is frequently derided, dismissed, or neglected; however, upon listening, the album reveals magnificent songs, performed with brilliance. It will be interesting to see if the recent biopic and, if it is released, the long-rumoured “Villager” box-set lead to a critical reappraisal.

Amongst other gems, the album features superb songs about relationships, such as "One Too Many Mornings" and "Boots of Spanish Leather". Then there is the anthemic title song, which rallies the young against the old, and arguably the finest of all so-called protest songs, "The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll". Other "street ballads" include both first- and third-person narratives, as seen in "North Country Blues" and "The Ballad of Hollis Brown".

I discussed "North Country Blues" in Dylan and Shakespeare: In The True Performing of It (hereafter, True Performing), when exploring the unique qualities of bards: “Burns and Dylan also display this ability. Being Bards, they too can adopt the voice and persona of others in an utterly convincing manner. Consider Burns as a young man known for his promiscuous lifestyle, putting into words and song, adapted from a luridly bawdy folk source, the touching view of a wife looking back on a long, faithful marriage and towards a joint ending of life in “Jon Anderson, My Jo”; or the young man, Bob Dylan, putting into words and song, again based on a folk source, the pitiful lament of the abandoned wife and soon to be abandoned mother of ‘North Country Blues” ”.[i]

"North Country Blues," as the title suggests, does not adhere to the ballad form, but it shares its opening and content with the socially critical 16th-century street ballad tradition. The song begins with the classic balladmonger's call for attention: "Come gather 'round friends," mirroring the album's opening line: "Come gather 'round people." Unlike the opening track, this is not an anthem, but a narrative of the despairing plight of common folk. Dylan embodies the persona of a woman who has "seen her whole life go down," as he sings elsewhere. She has lost her parents and her brother and will lose her husband, her children, and her entire town to abject poverty, its consequences, and the devastation wrought by a monetary system controlled by distant and indifferent figures. In this way, the song presents the "friends gathered 'round" with a tale of social distress akin to those lamented by balladeers of old. Here, he introduces it as a song about an iron-ore mine in an iron-ore town:

Bob Dylan - North Country Blues (Live At Newport Folk Festival - 1963) - 4K Restoration

Dylan has always excelled in performing traditional ballads, here is an early “Barbara Allen”, to go along with the one from 1988 I posted in an earlier episode of this series:

While it is true that Dylan went on to even greater achievements, we should not forget or underplay what was glorious in the period prior to the sublime albums of 1965 and 1966.

Money, Money, Money

The debate surrounding commercialism in popular music – the very "pop" in "pop music" – has led to some peculiar situations. The centrality of "selling out" (to commercialism) in the narrative of Dylan's "Judas" moment was something entirely overlooked in the film A Complete Unknown. One presumes that at two hours, and aiming for box office success ("sellouts!"), it was too vast a topic to address adequately. The late and much-missed C.P. Lee's Like The Night (Revisited): Bob Dylan and the Road to the Manchester Free Trade Hall is highly recommended for those interested in the background to this period. This phenomenon led to the outraged fans depicted in Eat The Document, and it was this that prompted the comment that Dylan was "crawling in the gutter". The fan was not annoyed that Dylan was playing an electric guitar per se, but rather that he was making money from doing so: "crawling through the bloody gutter, just making a pile out of it: yeah, he’s making a pile out of people he pretends he’s for." [ii]

I discuss the relationship between commerce and artwork in True Performing: "Dylan and Shakespeare’s work is grounded in popular entertainment and in pleasing audience. That ‘work’ is both business and artistic. Genius can exist, they prove, alongside commercial acumen and the highest artistry is not incompatible with widespread popularity and live shows.

We have established that Shakespeare was first and foremost a jobbing dramatist. He was a writer, actor, collaborator and editor of texts whose purpose was to be acted on stage and to prove popular enough to keep audiences coming back to pay for more. His business was that of pleasing audiences to increase the company’s cash flow. Genius and commerce are not always separate despite our romantic myths of starving artists in tiny garrets. Dylan remarked to biographer Robert Shelton, in 1978: “…the myth of the starving artist is just that – a myth”. Genius can also be at the beck and call of the need for cold, hard cash. One thinks of Dostoyevsky producing the most extraordinary series of novels in order to settle debts, and of Charles Dickens’ mass-marketed outpouring of the most beautiful quality prose, at a time when it was valued by quantity, and paid by the wordage. As Samuel Johnson prosaically put it: “No man but a blockhead ever wrote, except for money.” Both Shakespeare and Dylan prove to be canny operators in the world of commerce. William Burroughs remembered meeting a young Dylan who described himself as having “a knack for writing lyrics” and that he “expected to make a lot of money”.

Shakespeare and Dickens, now so justly academically revered, earned their living by producing hits for all of society. They did not write just for the privileged or especially educated elite. They were paid because they kept their audiences engaged and entertained. In this regard, it is clear that Bob Dylan has followed in their footsteps." [iii]

In "Shakespeare the Balladmonger?" [iv], her detailed and comprehensive overview of Shakespeare's intersection with the ballad world, Tiffany Stern investigates whether Shakespeare actively fostered links between theatres and balladmongers or simply utilised existing connections between these two most popular forms of popular culture. Her research points strongly to the former being the correct answer. Stern focuses on three main connections: marketing within plays, play ballads, and theatres as venues for ballad-hawkers to sell their wares. The combination of all the possibilities these afford suggests strong commercial links between the two popular entertainment spheres.

Noting that his contemporary, Ben Jonson, had ballads from his plays and masques printed as Broadsides, Stern describes Shakespeare seemingly engaged in what could be interpreted as marketing ballads within his plays. Potential examples suggesting this include Bottom's desire in A Midsummer Night's Dream to have a ballad written about his dream and sung at the end of the play (perhaps it was, and was also on sale at the end, either inside or outside the Globe, or both). Falstaff's jest in Henry IV Part 2, about having his exploits printed in a ballad, would certainly generate interest in purchasing such a ballad if one were on sale. Less persuasively, Cleopatra’s talk in Antony and Cleopatra of: "scald rhymers" who will "Ballad us out o' tune" might just do the same.

Stern’s finest example of this comes from The Tempest, where she uncovers a direct allusion to a ballad that was currently on sale:

“In one play, Shakespeare even drew attention to the same ballad publisher referred to by Ben Jonson: John Trundle. In The Tempest, Stephano starts drunkenly singing ‘Flout ’em, and scout ’em’, but Trinculo complains ‘that’s not the tune’ (TLN 1477-80). The spirit Ariel then enters and plays the correct tune ‘on a Tabor and Pipe’. But Ariel is, in the fiction, invisible – meaning that Stephano and Trinculo do not know where this sudden music has come from:

Ste. What is this same?

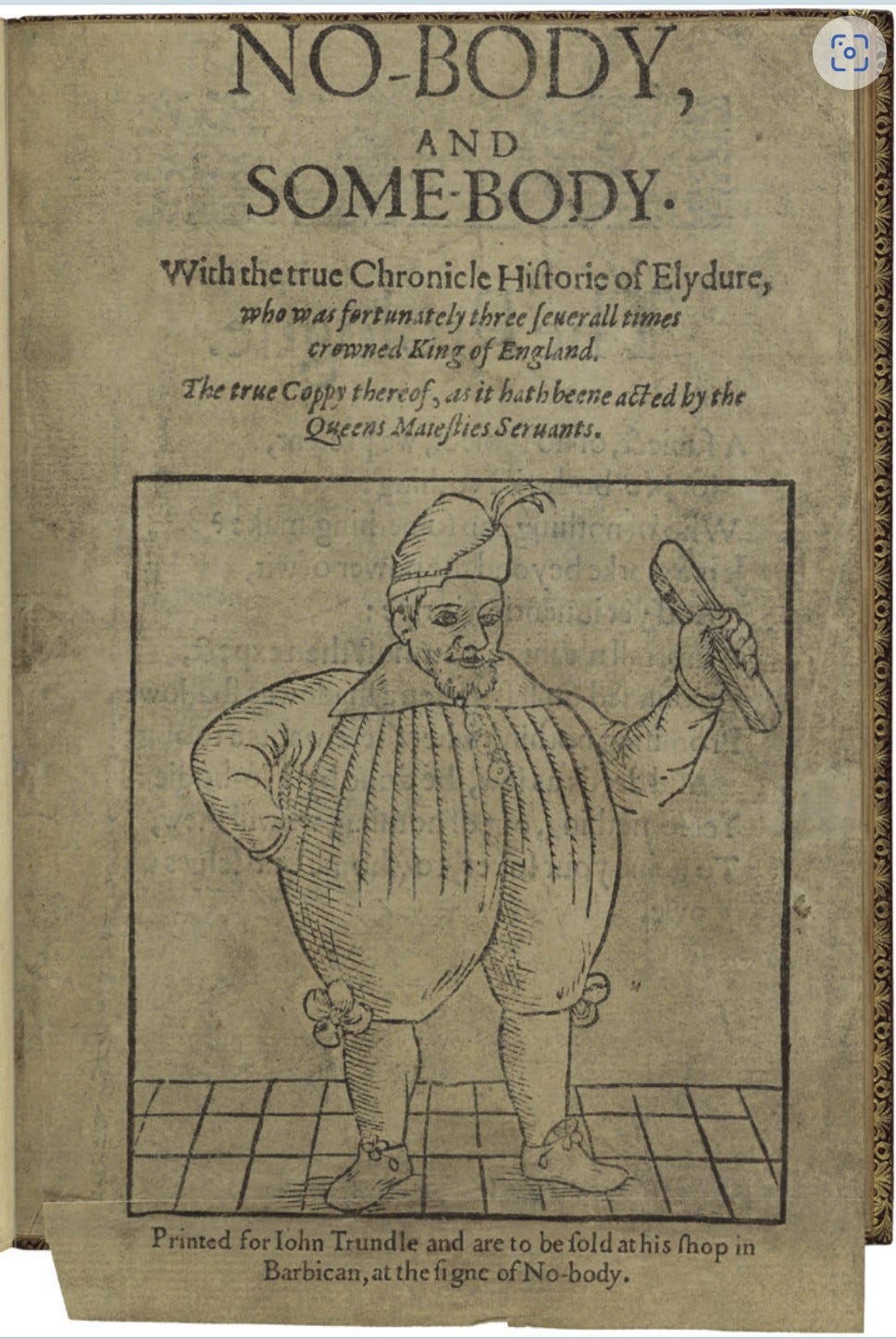

Trin. This is the tune of our Catch, plaid by the picture of No-body.

What is telling here, however, is that Trinculo does not straightforwardly refer to Ariel’s invisibility, ‘No-body’, but to ‘the picture of No-body’ (italics mine). That has a special meaning, for on 8 January 1606 the publisher John Trundle entered ‘The picture of No bodye’ in the Stationers’ Register; three months later, on 12 March 1605/6, he registered the anonymous play No-body and Some-body which, when printed, featured the picture of ‘No-body’ on its title page. He even started trading, as the title page of No-body and Some-body indicates in the colophon, at ‘the signe of No-body’. The reason for his fascination with the picture was, presumably, the fact that it was a visual joke: No-Body, has no body – just breeches up to his neck.

The Tempest’s reference to the picture of No-body, then, is simultaneously an acknowledgement that Ariel is invisible and a direct reference to John Trundle, presumably printer of the ballad being performed on stage. That makes Ariel, in this instance, the ballad-monger, and reveals a Shakespeare who used ballads to promote his play’s reach over time (any-one humming the tune is re-reminded of the play), in form (a paper ballad now doubles as a material souvenir of the production), and in cash (someone, Shakespeare, or Trundle, or the theatre, or a ballad-singer, perhaps all of them, will make money from this additional sale).”[v]

No-body, and Some-body title page (Printed for John Trundle and are to be sold at his shop in the Barbican, at the signe of No-body, 1606). A displayed here.

Play Ballads

Although Elizabethan London was exceptionally large for its time, it was small compared to modern cities. Both the theatre and printing communities, though booming, were small and tightly knit. A Venn diagram would illustrate a significant overlap between the two. Printers published the two primary subjects of my series of articles - plays and ballads - and, furthermore, the same printers would publish the playbills that advertised upcoming performances, alongside what Tiffany Stern describes as "play ballads":

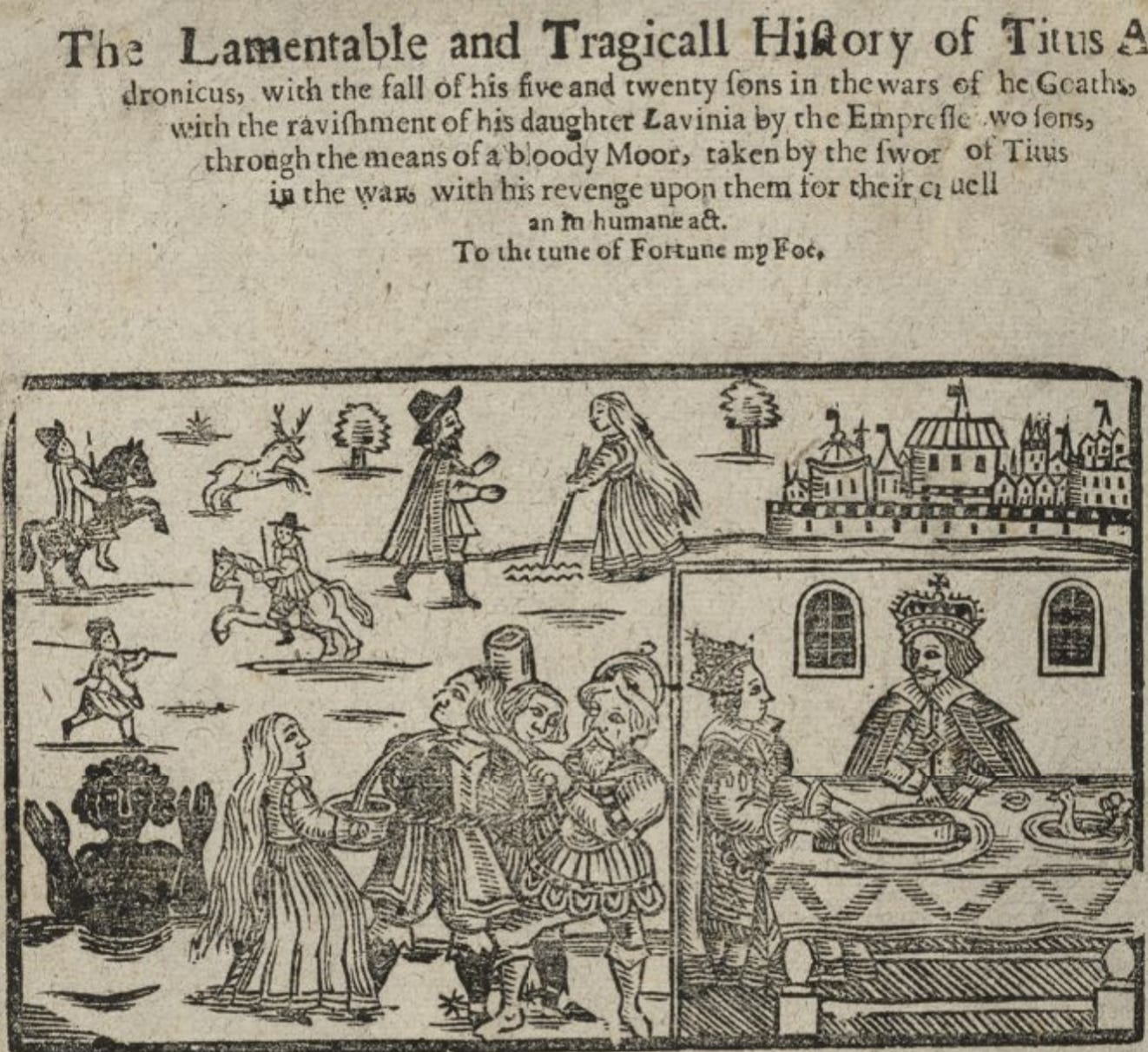

“..one that told the story of the play. There is, for instance, an entrance on the Stationers’ Register on 6 August 1596 for ‘A newe ballad of Romeo and Juliett’. Though that ballad is lost, it was presumably inspired by Shakespeare’s … Romeo and Juliet, in performance at the time, but not published as a playbook until the following year. By design or circumstance, the ballad of Romeo and Juliett will have advertised the play in performance, and potentially constituted one of its mementos. Ballads might equally advertise books. There is a double entrance on the Stationers’ Register of 6 February 1594 for John Danter who records not just ‘a booke intituled a Noble Roman Historye of TYTUS ANDRONICUS’ –Shakespeare’s play – but ‘the ballad thereof’. He intends to publish both together, apparently expecting playbook and ballad to co-advertise one another. That gives evidence, then, of ballads printed apparently to advertise (or batten on) performance; and ballads printed to advertise (or batten on) a printed text.”[vi]

The survival of multiple versions of a ballad for Titus Andronicus, some featuring woodcuts depicting scenes from the play and even a London theatre, suggests that these ballads served as advertisements, plot summaries, or souvenirs of a Globe performance:

“In its top right- hand corner is a depiction of a city which has, as its focal point, a large round theatre with its flag raised for performance. This picture seems, then, to refer not so much to Rome, the fictional city in which Titus Andronicus is located, as the factual city in which Titus can be seen as a play, London.”[vii]

Shakespeare was exceptional in being an actor, author, and sharer in his acting company (first The Lord Chamberlain’s Men, then later The King’s Men), remaining with the same company of actors throughout his career. The artistic benefits accrued from this were enormous, and his settled and profitable status perhaps also afforded many opportunities for self-advancement. Tiffany Stern continues by speculating that: “These examples may show Shakespeare, individual in so many other ways, having a private, individual relationship with ballad publishers and/or singers, that involved channelling work to them – which he had sometimes also written – himself. Alternatively, as he was financially invested in the success of his company – he became one of its ‘sharers’ in 1594, and a ‘housekeeper’ in its buildings from 1599 – it may show him exploiting and teaching the use of ballads as pre- play publicity, plot summaries, or/and as post- play souvenirs.”[viii]

As noted above, there was more than one ballad written on the tragic and gory tale of Titus Andronicus. This one clearly followed Shakespeare's play and compresses the very gory tale into an 18-minute bloodbath:

It is noteworthy from the above research that the ballad could have a wide range of interactions with a play; it could be a souvenir, an advertisement, or an extension. As far as commercial links are concerned, "crossover" is beginning to sound like "business as usual". Both forms of popular performance entertainment were becoming ever more interlinked with the expanding world of print. That these printed artefacts were aimed at the same audience can be seen in their shared subject matter and the similar textual temptations - "most lamentable", "most excellent", "the true and tragical tale..."-that both used to entice buyers. A broadside ballad cost a penny, as did entrance to the Globe as a groundling.

Balladmongers, wide-ranging both geographically and across social classes, had an existing sales terrain perfectly suited to spreading all of these; to help make a play a hit and to help cash in on it once it was one. This leads to further speculation from Stern:

“But given that Shakespeare often used ballads, and sometimes apparently wrote them, and given that all such ballads if printed would double as souvenirs and advertisements – while also making money in their own right – it is worth exploring further whether the theatre- ballad link might have been an intentional aspect of playhouse marketing.”

And:

“.. the word ‘balladmonger’ (‘monger’ meant ‘trader’) in the period sometimes indicated a ballad-seller and sometimes ballad-writer, Shakespeare emerges as at least one form of balladmonger, and perhaps both. That raises questions about how to interpret ballads 1) in plays and 2) about plays. As the only published bits of play generally available at the time of performance are ballads – in and about plays – are they a part of theatrical marketing or cross-marketing?” [ix]

Theatres as Selling Places for Ballad Hawkers

Turning now to the benefits the theatrical environment afforded balladmongers, Stern postulates a strong commercial relationship between playhouses and the ballad trade. Contemporary accounts describe the presence of ballad hawkers at theatre entrances, capitalising on the crowds attending performances. Caralyn Bialo explores the same relationship, describing how ballad sellers contributed to the festive atmosphere around theatres, relying on showmanship to attract audiences, mirroring, now in the city, their actions as itinerant hawkers traversing the countryside. This ensured that the theatre audience had a song-saturated day even before their ballad-filled plays commenced.

From the same study on Ophelia, What Does This Song Import?, quoted earlier in this series, Bialo vividly conveys an imagined scene:

“When Ophelia first appeared on the Globe stage, the traditional proximity of minstrelsy, balladry, and playing was perpetuated on the streets outside the theater in Southwark. The suburb was hospitable to the population likely to become ballad sellers for some of the reasons that it appealed to the professional theaters; civic and guild administration was slow and ineffective across the river. With a fluid population of migrants and an economy grounded in small-time trading and victualling, Southwark became home to what Natasha Korda calls an "informal theatrical economy": "Female hawkers, foreigners and aliens, who were excluded from the formal economy" worked alongside "theater entrepreneurs and professional players, many of whom were freemen, but who nonetheless sought to profit from unregulated commerce." Players and playwrights, minstrels, ballad singers, pawnbrokers, and bear wardens were mutually dependent, and ballad sellers helped create the festive atmosphere that drew Londoners to the Bankside.” [x]

Speculative though all this is, it does raise very interesting questions about whether theatres tacitly allowed, actively encouraged, or even financially benefited from these ballad sales, perhaps through concessions similar to those for food, drink, and other printed material. The diary of Philip Henslowe, owner of the Rose Theatre in London during the 1590s, survived and is an invaluable source of information about the workings of the Elizabethan public theatres.

Stern quotes two occasions where subcontracting is apparent: “Henslowe in 1587 ‘will not permit . . . any person . . . other than . . . John Cholmley . . . to utter, sell or put to sale in or about the . . . playhouse . . . any bread or drink’; while at Whitefriars 1607/8 ‘if any . . . profit can or may be made in the said [play]house either by wine beer, ale, tobacco, wood, coals, or any such commodity, . . . Martyn Slater . . . shall have the benefit thereof’”[xi]

Ballads, then, can be seen to have had a multifaceted and complex interaction with the plays of Shakespeare. They are embedded, either wholly or in part; they are used for the jig to end the plays (more of that in a future piece); they can act as souvenirs or marketing tools; they can continue the narrative and "extend the franchise," serving as neglected extensions of the plays themselves, or something in between. The significance of balladry in the experience of theatre in the sixteenth and seventeenth century was profound. As such, it is unsurprising to find Shakespeare’s mind pondering the significance of it all in his play The Winter’s Tale, and even less surprising to discover he dramatises those thoughts via characters on stage, as we shall see in the next article in this series.

Substack Outro

Thanks to Timothy Drake for alerting me to a podcast episode from ‘Shakespeare Unlimited’, covering some of the same terrain as I have been, on "Top 100 Pop Songs of the 1600s". Christopher Marsh, Professor of Cultural History at Queen’s University, Belfast, is quoted in the podcast: “Shakespeare clearly knew ballad culture very intimately. There are lots of references to ballads in his plays. I mean not necessarily just to the ones that made it onto our website, but the famous Desdemona’s “Willow Song” in Othello and she says “ the song tonight will not go from my mind” and I think we've all had that that experience of a of a song that won't shift. And, in A Midsummer Night's Dream, Bottom wakes from a vision and says he's going to get Peter Quince to write a ballad about it. So, the idea of kind of writing ballads about funny things that have happened is very much part of Shakespeare's world. And I think he's really tapped into… I mean, he was clearly very musical and he knows that ballads are happening and that they're developing and he clearly follows this closely.”

Podcast and links to “Hot 100” Ballad chart are here:

https://www.folger.edu/podcasts/shakespeare-unlimited/top-pop-songs-of-the-1600s/

© Andrew Muir, May 2025

[i] Muir, Andrew Bob Dylan & William Shakespeare: In The True Performing of It, Red Planet Books 2019 and 2020.

[ii] See Muir, Andrew Bob Dylan & William Shakespeare: In The True Performing of It for a detailed analysis of this situation and its many ramifications.

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] Stern, Tiffany, “Shakespeare, The Balladmonger?” in Bloomsbury Collections - Rethinking Theatrical Documents in Shakespeare’s England.

[v] Stern, Tiffany,” F. W. Bateson Memorial Lecture cgac023.pdf

[vi] Stern, Tiffany, “Shakespeare, The Balladmonger?” Bloomsbury Collections - Rethinking Theatrical Documents in Shakespeare’s England.

[vii] Ibid.

[viii] Ibid.

[ix] Ibid.

[x] Bialo, Caralyn “Popular Performance, the Broadside Ballad, and Ophelia's Madness”, https://muse.jhu.edu/article/510541/summary

[xi] Stern, Tiffany, “Shakespeare, The Balladmonger?” Bloomsbury Collections - Rethinking Theatrical Documents in Shakespeare’s England.