3. What does this song import?

Part 1 “Ophelia” and Part 2 “Nettie Moore”

OPHELIA

Introduction

No-one opened my eyes more to the intertwined world of popular ballads and Shakespeare’s plays than Tiffany Stern. We will return to some of her superb research at the conclusion of this series, but for now we have her explaining the significance of one of the many ballad or ballad fragments, that populate Hamlet. We saw in my last posting how Desdemona’s The Willow Song” relied on the audience knowing the mournful love ballad on which it was based. Similarly here, claims Stern:

“Another play seemingly reliant on broadside knowledge is Hamlet. In all three surviving texts of Hamlet, variant in so many ways, Hamlet recites, or perhaps sings, sections of Jephthah Judge of Israel: ‘One fair daughter and no more, / The which he loved passing well’, ‘as by lot, / God wot’, ‘It came to pass, / As most like it was’ (Hamlet, 2.2.343–56). He too seems to expect detailed knowledge of the ballad’s whole first verse[i]:

I Read that many yeares agoe,

when Jepha Judge of Israel,

Had one faire daughter and no moe,

whom he beloved passing well:

And as by lot God wot,

It came to passe most like it was,

Great Warres there should be,

and who should be the chiefe but he, but he.[ii]

The many prompts that Hamlet gives seem designed to position Polonius as Jephtha, bad judge, and misguided chief in a war – the ‘war’, in Hamlet terms, being the brewing conflict between Claudius and Fortinbras, or the local battle between Claudius and Hamlet. And, as Jephtha, in ballad (and bible, of course) promised to pay for his victory by sacrificing the first living thing he comes across – only for it to be his virgin daughter – so Polonius, the parallel suggests, will end up sacrificing Ophelia. This seemingly marked and insistent use of intertextuality to enrich subtext, however, only works if the audience have comprehensive knowledge of – and perhaps easy access to – the ballad text itself.”

It is worth noting, above and beyond the detail of the intertextuality and the audience’s ballad familiarity, the possibilities raised from it being natural for the Prince of Denmark to sing and the suggestion that audience may have “easy access” to the ballad sung on stage. The prevalence of song throughout the play is something you would almost certainly not have been taught if you learnt the play at school, but it is how the play was written by Shakespeare. The director Robert Icke was one who was well aware of this and in his hit production for the Almeida Theatre he carefully placed a number of Dylan songs throughout the play. I was lucky enough to catch it in its second consecutive sold-out run at the Harold Pinter Theatre. A version was broadcast by the BBC in which the Dylan songs, if memory serves me well, took up less time though were still a prominent feature. The songs included were: “One More Cup Of Coffee”/ “Up To Me”/ “Spirit on the Water”/ “One Too Many Mornings”/ “Sugar Baby” and “Not Dark Yet”. [iii]

Stern goes on to remark: “Hamlet is, of course, a ballad-focused play. In it, mad Ophelia also performs well-known ballads.” It is to the songs Ophelia sings in Act IV scene v that we now turn; partly because this expands on my previous article on “The Willow Song” and Othello, partly because it showcases the staging of a ballad performance within the play and partly because there is such a concentration of song in this scene during Ophelia’s two appearances, where she expresses herself through balladry.

Within the complex tapestry of the play, the character of Ophelia often stands as a figure of tragic innocence, overwhelmed by the events unfolding around her. However, a closer examination of her descent into “madness”, particularly her use of song, reveals a more nuanced and potentially subversive dimension to her character. Drawing on the vibrant culture of broadside ballads, Shakespeare crafts Ophelia's mad scenes not merely as a descent into incoherence, but stages them as a metatheatrical commentary that provides a potent lens through which to view female experience within a patriarchal society.

As is natural in performance art, productions vary greatly. I provide two links here to differing modern takes on the scene:

Hamlet - Act 4 Scene 5 - "I will not speak with her" (Subtitles in modern English)

Hamlet • Act 4 Scene 5 • Shakespeare at Play

Whatever the merits of these, neither give the full impression of Ophelia on stage in Shakespeare’s time. The stage directions tell us[iv]: Enter Ophelia playing on a lute, hair down, singing and she has two audiences: cast and audience. She will, before the conclusion of her “act”, lead the crowd in a sing-along to a refrain popular from many a bawdy ballad. This active solicitation of participation directly echoes the practices of ballad sellers who would encourage passersby to join in on familiar refrains.

What does this song import?

Critics have long pondered whether Hamlet was mad or feigning it, and, if so, to what degree. The agency was given to the character in these discussions. Contrastingly, with Ophelia madness was taken as absolute. Even when it became ever clearer, as research developed over time, that her songs and her flowers were all presented with apt meanings and allusions, this was written as Shakespeare telling us, through cryptic ‘nonsense messaging’, Ophelia’s innermost feelings. Of course, it is always Shakespeare in the cases of both characters, but the different approach in criticism until relatively recently is instructive, with Ophelia, reflective of how she is treated by other characters in the play, accorded none of the respect given to Hamlet.

When you take the character of Ophelia more seriously, you find that through her ballads, flower-gifts and interaction with the audience, an individual with agency and an important message emerges. As well as their symbolic meanings, the flowers Ophelia distributes and talks about include ones well known to her audience for use in contraception, abortion, and treatment for syphilis[v]. Something to keep in mind. perhaps, when listening to her “St Valentine’s Day” song.

Ophelia is not treated as individual in the play by the other characters. Instead, there she is talked at, talked to, talked down to, talked over, and talked about but never talked with in a meaningful sense. The others treat her as a stereotyped representative figure of ‘demure woman’. Ironically, when she dies, when she ceases to be an individual, the other characters think of her personality for the first time. We, the audience, thanks to the songs she sings, whose message they fail to recognise, get there a little ahead of them. Prior to that, as Rosalyn Stilling puts it:

“Her forced receptiveness in conversations with males represents the patriarchal idea of a woman’s position of receiving male initiative. Her life is not her own; it is owned by every man and powerful figure around her. She tries to be the passive, obedient and submissive maiden society demands of her, but in doing so, she loses her agency and identity because she is not free to discuss her relationship with her family.” [vi]

Ophelia's voice is consistently marginalized until she employs songs to express her inner thoughts, after conventional discourse and society at large has failed her.

When Ophelia descends into what is routinely dismissed as "madness" she is alone, no longer controlled by her father (killed by her boyfriend), her brother (still far away, as far as she is aware) or her boyfriend (sent away by the king, to be killed). Stilling argues that her madness is not necessarily a psychological disturbance but rather a multifaceted response to her objectification, abandonment, and sorrow. In this state, Ophelia, rather than simply going mad, gains a voice through songs and the symbolic language of flowers, both traditionally linked to feminine expression and sexuality:

“Instead of responding directly to Gertrude’s and Claudius’s questions, Ophelia's songs are all applicable to her life, which should not be the case for someone supposedly mad. In this way, the ever-obedient Ophelia, through experiencing heartbreak and abandonment, breaks the chains of her receptive and timid nature by choosing to say what she wants rather than what Gertrude wants.”[vii]

There is a fear over Ophelia’s behaviour, but what immediately concerns the onlookers is what she may say rather than her mental health: “'Twere good she were spoken with; for she may strew/ Dangerous conjectures in ill-breeding minds.” The corrupt Danish Court is not a centre of power that can bear any light being shown upon it.

Ophelia’s songs, in order

Editor G. R. Hibbard tells us that: “The songs Ophelia sings are not known elsewhere, with the single exception of the lines: How should I your true love know/From another one? However, they smack very strongly of the traditional ballad, in which love - especially lost or unrequited love - and death were the leading motifs. The likeliest explanation of their origin is that Shakespeare took snatches, as the queen calls them, of old songs and wove them together to fit his own purpose, for they do render in a manner which is both poignant and haunting the two causes of Ophelia’s madness - Hamlet’s rejection of her love and the death of her father killed by his hand. Inextricably involved with one another her two losses compete for attention in her mind…” [viii]

Ophelia’s singing begins with:

How should I your true love know

From another one?

By his cockle hat and staff,

And his sandal shoon.

The Queen interrupts, and asks “Alas, sweet lady, what imports this song?”. However, in a complete transformation of her former obedient and submissive character, Ophelia demands that she be listened to and continues to sing:

He is dead and gone, lady,

He is dead and gone;

At his head a grass-green turf,

At his heels a stone.

O, ho!

Test

Ophelia again responds to attempts to silence her by continuing to sing; it is her time to tell her story and she will not be deflected from doing so.

White his shroud, as the mountain snow

Larded with sweet flowers

Which bewept to the grave did not go

With true-love showers.

Ophelia's choice of ballads is not arbitrary. The excerpt Hibbard quotes as “known lines” come from the hugely popular "Walsingham Song", which, with its theme of abandoned love, resonates with her relationship with Hamlet[ix]. These lines are the first Ophelia sings, suggesting that her distress stems not only from her father's death but also from her abandonment by Hamlet. The later line "He is dead and gone, lady" connotes her father, but as she begins by singing of “true love” and goes on to sing of “true-love shower”’ reinforcing this as more of a mournful love ballad than (just) a daughter’s lament for her lost father.

Shakespeare thus conveys through Ophelia an intimate sense of loss that intertwines her grief for her father with her grief for Hamlet. There is even a quick improvisation when Ophelia realises that her father’s burial did not follow the lines she was singing and so she inserts a negative into the second of these lines: “Larded with sweet flowers/Which bewept to the grave did not go”. Again, this quick-thinking and apt change are not something you would expect from a deranged mind. She is deeply traumatised, but she is not senseless.

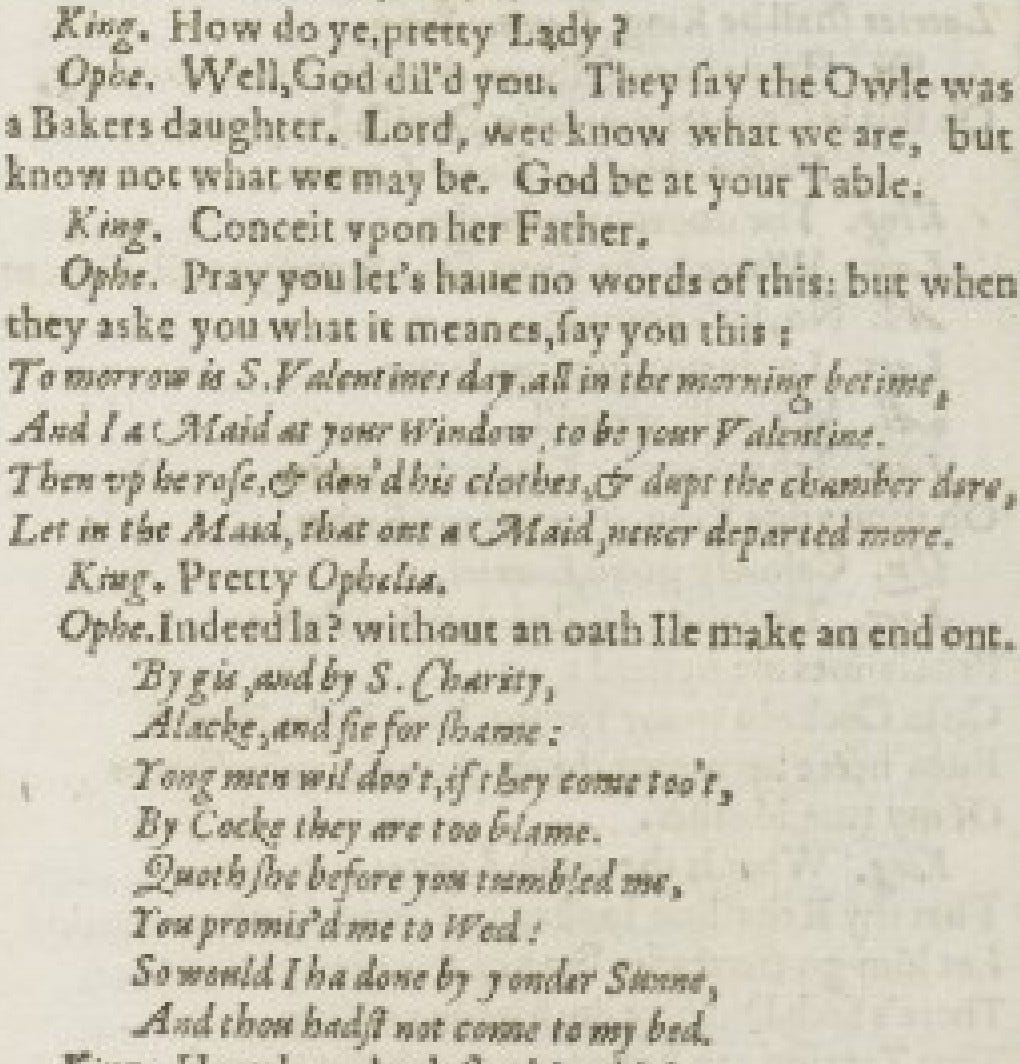

The lyrics of Ophelia's songs are not, then, random ramblings, but are closely connected to her experiences and offer a critique of woman’s place in the Danish court and society and, by extension, those of England at the time of performance. There has been no ballad yet found of her next song, and it is generally now taken to be one that Shakespeare wrote to suit his purposes as there was not one to hand that the audience would already know[x]. Original, or not, the “St Valentine's Day” song is a recognizable ballad form directly relating to recurrent love ballad themes of sexual desire, and potential loss of virginity. The maid in the song goes to her lover on St Valentine’s Day to have sex; Ophelia's singing again reflects her own situation regarding her desires for Hamlet. However, critics are divided on whether she is revealing that she lost her virginity to Hamlet or that she wanted to but that her social situation meant she had to suppress those desires and laments now that she never got to express them.

While broadside ballads could sometimes reinforce patriarchal norms, they also provided a crucial space for the articulation of female desires and anxieties. After the King’s interruption, Ophelia “makes an end” that begins in traditional fashion by claiming men “are to blame”, but ends with the revelation that the woman had gone to the man’s bed, reflecting back to the opening when she went to his bedroom on St Valentine’s Day. The man then refuses to marry her because she took the pre-marital initiative, and because presumably she is “damaged goods” even though he was the one who “damaged” them. Ballads were one of the very few places where women could express themselves on such subjects.

In traditional ballads featuring lower-class women, it is not uncommon for a female character to "succumb" to the advances of a persistent young man, often one she desired from the beginning. This can have catastrophic results for her, but not always so and sometimes it ends very happily, or life continues without undue drama. A similar pattern appears in James Joyce’s Dubliners story “The Boarding House,” where a mother strategically enables her daughter’s liaison with a young man. When the daughter becomes pregnant, the man is socially compelled to marry her. Here, too, societal pressures are evident, but notably, it is the man who finds himself ultimately constrained by them.

By contrast, in ballads and plays featuring women of higher social standing, yielding to temptation typically results in far more severe consequences (the Eve story, again) and Ophelia was under threat of ruin if she behaved in this way. This is made abundantly clear in the play and it is something that would have been assumed to be the case by the audiences of the time.

To-morrow is Saint Valentine's day,

All in the morning betime,

And I a maid at your window,

To be your Valentine.

Then up he rose, and donn'd his clothes,

And dupp'd the chamber-door;

Let in the maid, that out a maid

Never departed more.

KING CLAUDIUS

Pretty Ophelia!

OPHELIA

Indeed, la, without an oath, I'll make an end on't:

Sings

By Gis and by Saint Charity,

Alack, and fie for shame!

Young men will do't, if they come to't;

By Cock, they are to blame.

Quoth she, before you tumbled me,

You promised me to wed.

So would I ha' done, by yonder sun,

An thou hadst not come to my bed.

Just as he did with Othello and Desdemona, Shakespeare leaves open the question of whether Hamlet and Ophelia have had sex. It is up to directors and actors to decide how they will play this and, as is natural in performance art, it changes from production to production. I have seen productions where it is clear they have and ones where it is clear they have not and Ophelia is singing from frustrated longings. I would even say it is quite likely that I have felt both possibilities in the same performance, in the earlier and later scenes, without being disturbed by the seeming contradiction. Performing art makes this possible, only when sitting in a study reading, does it become an issue of concern. We are watching a play, after all, that includes a ghost who first appears in armour and can be seen by all but when he next is seen is dressed in ordinary clothes and can only be seen by his son. The magic of performance, the ephemerality of the moment allows not only ambiguity but not also paradox, as noted in previous posts in this series and elsewhere.[xi]

Staging Ophelia’s performance

Ophelia leaves the stage and re-enters for her second set of songs. It is all very carefully managed; her performance is a staged show within a stage show. Before we hear her sing, Horatio describes her behaviour as that of someone intending to captivate onlookers and introduces her upcoming performance to cast and audience alike.

Carolyn Bialo foreshadows a later theme in this series when she expands this metatheatricality to encompass the scenes outside the playhouse, even before the performances begin:

“When Ophelia begins to sing, her performance within the play reproduces on stage the idioms of ballad sellers around the theater. Ballad sellers opened their songs with invitations to passersby to stop and listen, and they closed with invocations to buy the broadside text. Music and lyrics were circulated simultaneously in multiple ballads, and ballad sellers asked their audiences to sing along with well-known refrains. Similarly, Ophelia enters the Court demanding audience attention, specifically from Gertrude, and she departs with a formal adieu: "Good night, sweet ladies, good night, good night" (IV.v.70). In the meantime, she demands that her onstage "hearers"—and by extension, her Globe audience—participate in her burdens: "You must sing A-down, a-down'; and you 'Call him a-down-a- (IV.v.171-3; italics mine). Globe spectators were likely familiar with Ophelia's "snatches of old tunes" and able to hum along in their places. They may even have strolled among peddlers singing precisely Ophelia's refrains as they entered the theater.”[xii]

Ophelia’s second set of songs begins with another mixture of fatherly and romantic lamenting love:

They bore him barefaced on the bier;

Hey non nonny, nonny, hey nonny;

And in his grave rain'd many a tear:--

Fare you well, my dove!

After an interruption, she continues with:

You must sing a-down a-down,

An you call him a-down-a.

O, how the wheel becomes it! It is the false

steward, that stole his master's daughter.

Ophelia earlier made a remark on “the owl and the baker’s daughter” just before singing the St Valentine’s Day song. This appears to have brought the ballad “The Miller in His Best Array" to Ophelia’s mind. Reminiscent of the Joyce story above, the baker’s daughter plays hard to get but is intending to be “caught” all the while. The frank embrace of pleasures of the flesh are celebrated in a chorus which was shared with other popular songs of the time. Bialo comments:

“…she resorts with the miller to his mill where they "will merrye be" and "daunce a downe," a playful euphemism for sex that was a common ballad refrain. The maid decides that dancing "a downe" is "the prettiest sport in all this towne." Ophelia uses precisely this refrain when she invites her audience to sing along with her in Hamlet. "You must sing 'A-down, a-down'; and you 'Call him a-down-a’ (italics mine) she insists, echoing the language in which ballads not only depict but also condone lower-status women who enjoy sexual intimacy.”

Before her final song which reflects grief for her father,[xiii] Ophelia sings an intriguing single line: “For bonny sweet Robin is all my joy.” The ballad “Bonny Robin” is referred to in other plays of the time, though no copy has ever been found. Additionally, however, Robin, as a male name, like the later “Willie”, also carried the same lewd connotation of Ophelia’s earlier use of “Cock”, both being double entendres for penis. This usage appears in various plays and ballads of the time, including Shakespeare’s Henry IV part 2.[xiv]

Ophelia's ballad singing, much like we saw with Desdemona's "Willow Song" in Othello,[xv] has the potential to evoke a sense of shared female experience within the audience. The themes of lost love, betrayal, and societal constraints resonated with the experiences of women in the Elizabethan era. By singing these familiar tunes, Ophelia links her personal anguish to a broader expression of female vulnerability within a patriarchal society.

Caralyn Bialo, in discussing Ophelia, also uses the example of Desdemona's "Willow Song” in Othello, which becomes a symbol of female solidarity and a counter-voice to male misogyny, to suggest that Ophelia's ballads similarly allow for a reading where her tragedy stems not only from Elsinore's corruption but also from a broader patriarchy demanding her complete submission. By speaking through the genre of the ballad, Ophelia's voice becomes one among other female voices, potentially appealing to the women in Shakespeare's audience.[xvi]

There is also the contrast of Desdemona singing in private (acceptable female behaviour for her time and social position) and Ophelia singing impromptu and in public, which would have been far more transgressive. The startling combination of themes in her songs - love, lust, bawdy puns and paternal loss - intensifies the scandal and would have electrified the crowd. Yet we must also recall that the singer on stage was, in fact, a boy actor playing a woman, which adds additional layers of theatrical and cultural complexity.

To conclude, a familiar cultural language

These songs were not random; they were deeply rooted in the popular performance tradition of broadside ballads, the "pop songs of his day". What Gertrude calls "snatches of old tunes" are carefully brought together. Despite her distracted state, Ophelia is not incoherent nor rambling; but instead is expressing her situation and the traumas she has lived through via the familiar cultural language, open to, and enjoyed by all, of the popular performance tradition of broadside ballads, the “pop songs”.

We often read of Shakespeare’s plays within a play (the Mousetrap scene in this very play, for example). This metatheatrical episode is similar, but this time it is the staging of a ballad seller’s performance, something connected to but outside the main flow of action. A startlingly fresh new viewpoint is opened and the spectators’ involvement is introduced by Horatio and demanded by Desdemona. This new viewpoint allows a female perspective, tied to ballads and feminine participation in those, into proceedings. That Shakespeare’s audience recognised the tunes and themes of her songs meant that there was a direct connection between them and Ophelia, making her plight all the more relatable and impactful. Despite Ophelia’s situation, it must have been a release from the dark main narrative for the audience to find themselves humming along to familiar tunes and joining in on a lusty chorus.

Ballad culture provided Shakespeare with a rich and multifaceted tool to develop Ophelia's dramatic function. It allowed him to portray her “madness” in a way that was both culturally resonant and deeply expressive. Ophelia's mad songs, far from being mere fragments of a shattered mind, represent a sophisticated deployment of popular cultural forms by Shakespeare. By staging what resembles a ballad seller's performance, he not only blurs the boundaries between theatrical traditions but also provides a powerful platform for a female perspective. Through the familiar melodies and resonant themes of broadside ballads, Ophelia provides a poignant commentary on the constraints and tragic realities faced by women and invites the audience to engage with her plight on both an emotional and a cultural level.

What does this song import?

Part 2 “Nettie Moore”

Listen: Dylan’s “Nettie Moore”

(other featured songs, if not embedded, are to be found at the foot of the article)

***

The release of Modern Times in 2006 marked a distinctly different experience for me compared to all of Dylan’s albums since 1990’s under the red sky. From that album onwards, I had written extensively about each new release and continued to revisit them for subsequent book projects. By the time Modern Times arrived, however, my second fanzine was winding down, and I found myself exhausted by the relentless cycle of Dylan research, commentary, and news. So, rather than pore over the lyrics, I simply sat ‘on that ol’ bank of sand and just listened to the vocals flow’. As relaxing and enjoyable as that was, the experience reinforced a simple truth: the more effort one invests, the greater the rewards.

“Nettie Moore” stood out from the start and remains my favourite track to this day. Yet I did not fully grasp what was happening in the narrative until I read Sean Wilentz’s insightful commentary in Bob Dylan in America. In retrospect, my initial disengagement feels almost shameful, especially given that the key to unlocking the song’s meaning lies precisely in the kind of intertextual balladry I’ve been exploring throughout this series.

I was still reading about Dylan, naturally, how can one stop, especially at the time of a new album release? Consequently, I knew that “Nettie Moore” had a source in an old song, from just before the Civil War, known as: “The Little White Cottage” or “Gentle Nettie Moore”[i].

Text - The little white cottage, or, Gentle Nettie Moore | Library of Congress

Song - Gentle Nettie Moore

This brought me back to familiar Dylan territory, once again into the fraught land of minstrelsy, the antebellum South and slavery[ii]. I assumed, without studying the situation, that the narrator in the Dylan song was the slave whose love (Nettie Moore) had been taken away after being sold by their master as described in the blackface song from 1857. I further assumed Dylan’s song featured him on the run trying to follow and find Nettie. This was all rather loose thinking, as I sat back and let the vocals wash over me. I was aware that much of the song did not cohere around this imagined scenario in my mind, but I let it go, I let it all go and luxuriated in the hypnotic melody with its rising hope followed by an inevitable-sounding, dying fall. An emotional cadence that brought these lines of Shakespeare to mind:

That strain again! it had a dying fall:

O, it came o'er my ear like the sweet south,

That breathes upon a bank of violets,[iii]

The narrator’s mood and the song’s lyrical trajectory mirror this dynamic: a pattern of rising hope, a pause, and then a crushing descent. The chorus assures us that “Winter’s gone,” yet for this narrator, there is no Spring to follow—only an unending darkness. Near the end of the song, he declares, “I'm standing in the light”, only to undercut it with a swift return to despair: “I wish to God that it were night.”

The captivating vocals were at their strongest for me at the heart-stopping pause in the chorus line: “I loved you then - - - and ever shall” which I thought beautiful and intuited was key to the song. I still feel the same way, not due to any revelation of my own, but to the aforementioned Wilentz’s critique in which he points out that:

“…he alludes to “Frankie and Albert” as fact, stone cold fact…There, in plain view, is a song of a lover’s murder: Albert is dead, and Frankie is raising hell.”

Just as Shakespeare relied on his audience’s familiarity with songs - either alluded to or partly sung in his plays - to convey the full story of what was going on in his characters’ minds, so Dylan here is calling on his listener to recall the well-known tale of “Frankie and Albert,” a song covered by many artists, including himself, to uncover the meaning of his narrator’s thoughts and memories. When we do, we find ourselves back in the land of murder ballads and, I fear, femicide. Drunkenness, infidelity, violence and a killing, all hinted at in the lyrics, though the narrator keeps shying away from those memories and switching to ones of love and carousing, plus dreams of a return to previously known peace. His mind won’t let him off so easily though:

Everything I've ever known to be right has proven wrong

I'll be drifting along

The woman I'm lovin', she rules my heart

No knife could ever cut our love apart

The narrator may claim love’s inviolability from the knife in a spiritual sense, but it has separated them, physically, forever and has set him on the road to a death sentence.

Here, once again, we hear the importance of ballad intertextuality directly impacting the meaning of the song (or play in Shakespeare’s case). The story of “Nettie Moore” is the story of interposed ballads and blues. From the opening scene of the drifter hobo, Lost John, corrected immediately with the warning, “Something's out of wack “ and the additional information, supplied by a Robert Johnson line, that this ‘lost John’ has a hellhound on his trail and the results will not be pretty.

That pursuing fiend now appears as guilt for killing his beloved (or, possibly, her lover). Is it the “Frankie and Albert” story, but with the genders reversed to the more common one of the man being the killer and the woman being the victim? There are suggestions of infidelity: “Don't know why my baby never looked so good before I don't have to wonder no more”, notwithstanding that the verse that this line introduces can be read two ways; though whichever way you take it, the imagery seems more sexual than victuals:

Don't know why my baby never looked so good before

I don't have to wonder no more

She been cooking all day and it's gonna take me all night

I can't eat all that stuff in a single bite

There are ominous threats remembered:

I'm going to make you come to grips with fate

When I'm through with you, you'll learn to keep your business straight

Yes, he still loves Nettie, he always has and always will but then the same can be said of Frankie, who still loved Albert even as she killed him:

Frankie got down upon her knees.

Took Albert into her lap.

Started to hug and kiss him.

But there was no bringin' him back.

He was her man but he done her wrong.

If I had been paying my usual attention when albums are released, then the Edna Gundersen interview would surely have jolted me into examining the song more closely. It would be helpful to hear Dylan speaking the quotes; however, I have no recording and so can only read them as printed. Talking of all the songs on Modern Times as a whole, Dylan said, “(These songs) are in my genealogy. I had no doubts about them. I tend to overwrite stuff, and in the past I probably would have left it all in. On this, I tried my best to edit myself, and let the facts speak. You can easily get a song convoluted. That didn’t happen. Maybe I’ve had records like this before, but I can’t remember when.” On “Nettie Moore” he remarked that it: “troubled me the most, because I wasn’t sure I was getting it right. “Finally, I could see what the song is about. This is coherent, not just a bunch of random verses. I knew I wanted to record this. I was pretty hyped up on the melodic line.”[iv]

I take this as a Dylan hint that one should look for a ‘coherent’ story through seemingly ‘random verse’ and that he is concerned people miss that. Jealous rage, whisky, a knife and an ending on the scaffold. This sounds like familiar terrain. I listen and ask myself if this what Dylan meant by: “Finally, I could see what the song is about. This is coherent, not just a bunch of random verses”.

The listener is taken through thoughts and conversations from memories, from different periods in his past, and the ‘coherent’ story that is there can only be followed by, what else, the quoting of other ballads and popular songs. It is still quite difficult to follow because the narrator does not want to remember, though he is hounded by the memory.

As my good friend, Bob Jope puts it: “‘The fragmentedness is in fact a product or even an expression of the speaker’s inability or unwillingness to articulate: the crime that he may have committed is something he both wants to admit to but cannot find words for. Instead, he remains in a purgatory of his own making.” And, again: “…the speaker in “Nettie Moore”, the adopted persona, is haunted by memory, this time guilt for something left unexplained – something he can’t explain or, more likely, can’t bear or dare to articulate. The monologist wants to talk but can’t find words to tell us why…”[v]

We are introduced to the main narrator, we see back in his mind that he was at a crossroads, we know – the music and vocals are more than enough to tell us before attending to the lyrics – that he chose the wrong path. Despite repeated yearnings and dreams he is never going to get back to Nettie Moore and the life they once had, just as the singer of “Gentle Nettie Moore” would never see his beloved again.

Albert's in the graveyard, Frankie's raising hell

I'm beginning to believe what the scriptures tell

Is he thinking here of “Thou Shalt Not Kill?” We are told he has “Got a pile of sins to pay for” and there is an abrupt change from all the swirling memories and dreams to the present, the inevitable ending that the persistent drum beat has been pushing the song towards, as “the Judge rises”. In the context of the song the judge is both an earthly one passing sentence for murder, and the heavenly one for the breaking of a sacred commandment. Yet, the singer still looks to heaven which seems odd at first, but it echoes that other killer in the song, Frankie from “Frankie and Albert” as well as resonating with the ending to “Gentle Nettie Moore” (the Little White Cottage) . ”

The “original” Nettie Moore closed with lines which bring Dylan’s “A lifetime with you is like some heavenly day” to mind:

You are gone, lovely Nettie, and my heart must surely break,

When the tears come no more into my eyes;

But when weary life is past, I shall meet you once again

In Heaven, darling, up above the skies!

Killers, too, look to heaven “when weary life is past”. In Lead Belly’s “Frankie and Albert”, we last hear of Frankie:

Once more I saw Frankie

She was sittin' in her chair

Waitin' for to go an' meet her God

With the sweat drippin' out her hair

Albert was her man, but she shot him down

Murder it would appear does not preclude a meeting with God. Lead Belly, in yet another intertextual use of song, references “Nearer My God to Thee”, and ties Frankie to it, in this verse:

Little Frankie went down Broadway

As far as she could see

And all she could hear was a two-string bow

Playing, "Nearer, My God To Thee"--

All over the town, little Albert's dead

Dylan retains this reference but transposes it to the end of his recording. Dylan brings a judge into his closing scene, as he does in Nettie Moore, and ends with Frankie unbowed:

Judge said to the jury.

"Plain as a thing can be.

A woman shot her lover down.

Murder in the second degree."

He was her man but he done her wrong.

Instrumental

Frankie went to the scaffold.

Calm as a girl could be.

Turned her eyes up towards the heavens.

Said, "Nearer, my God, to Thee."

He was her man but he done her wrong.

“Nettie Moore” concludes with the narrator utterly alone, and again the rising music gives way to a fall, a final fall this time. Now, we hear the lines “I'm standing in the light/I wish to God that it were night in the sense of: “Everyone who does evil hates the light, and will not come into the light for fear that his deeds will be exposed” (John 3:20), fittingly for a man who had been “beginning to believe what the scriptures tell’ :

Today I'll stand in faith and raise

The voice of praise

The sun is strong, I'm standing in the light

I wish to God that it were night

Oh, I miss you Nettie Moore

And my happiness is o'er

Winter's gone, the river's on the rise

I loved you then and ever shall

But there's no one here that's left to tell

The world has gone black before my eyes

If you have been following this series so far, you will have noticed certain motifs returning regularly. Two of Graley Herren’s three readings of Time Out of Mind appear in this song: namely, Herren’s themes of runaway slaves and femicide murder ballads. As with The Ballad of Donald White we have a subset of the murder ballad tradition, highly popular in Shakespeare’s Day, the “execution ballad”. (“Donald White” is not part of the series, but it is interesting how often it chimes with the ongoing articles.) Ambiguity, intertextuality, the primacy of performance and, to take us back to the start of the series (‘MTP – More True Performing), with “Matty Groves” and Dylan’s “Nobel Lecture in Literature” speech, a mention of Frankie just before the “Matty Groves” reference:

You know what it’s all about. Takin’ the pistol out and puttin’ it back in your pocket. Whippin’ your way through traffic, talkin’ in the dark. You know that Stagger Lee was a bad man and that Frankie was a good girl.

Lead Belly appears, most pertinently, later in the same speech: “somebody – somebody I’d never seen before – handed me a Lead Belly record with the song “Cottonfields” on it. And that record changed my life right then and there. Transported me into a world I’d never known. It was like an explosion went off. Like I’d been walking in darkness and all of the sudden the darkness was illuminated. It was like somebody laid hands on me. I must have played that record a hundred times.”[vi]

Lead Belly's name is a particularly perceptive one for Dylan to use on this occasion as the blues singer, and convicted murderer, had already found his way into the lofty sphere of literary acclaim. In the 1930s, John Lomax brought Lead Belly to several American colleges and universities, including a notable appearance at Vanderbilt University during a major gathering of literary scholars in 1934. More significantly, Lead Belly’s version of Frankie and Johnny (also known as Frankie and Albert) was included in the influential and long-standard anthology Understanding Poetry, edited by Cleanth Brooks and Robert Penn Warren, a cornerstone of the “New Criticism” that formed the bedrock of mid-20th century literary pedagogy.

Francis Dore, in her excellent account of these matters and their ramifications for Dylan scholars[vii], points out that the inclusion of “Frankie and Johnny” in Understanding Poetry is all the more resonant when we recall that John Donne, another figure referenced in Dylan’s Nobel Lecture, also features in the same volume. Together, Donne and Lead Belly form a striking dyad, perfectly encapsulating Dylan’s vision of his own artistic lineage, one rooted as much in the raw immediacy of vernacular performance as in the canon of high literary tradition.

***

To conclude, here is Lead Belly introducing and singing “Frankie and Albert” in 1940. It begins at about three minutes in. There are many other versions easily found on the internet, but I thought you good people would appreciate the whole recording here: 【TLRMC043】 Woody Guthrie & Leadbelly 12/12/1940

Dylan: Frankie & Albert

Lead Belly: “Cottonfields”

Substack Outro

Next time will see a turning away from specific killing or deaths in ballads (phew!), for the most part, and concentrating on why ballads were so vital and prominent on the Shakespearean stage in general, rather than particular examples. We all know why ballads are so important to Dylan, but the history of their inter-relationship with Jacobethan drama is worthy of investigation before we go on to look at Shakespeare’s own considered examination of the same topic.

© Andrew Muir, 2025

Thanks again to Bob Jope!

Endnotes:

[i] Bloomsbury Collections - Rethinking Theatrical Documents in Shakespeare’s England.

[ii] [A proper new ballad, intituled], When Jepha Judge of Israel; Manchester Central Library,

[iii] This performance is explored in chapter 7, “Dylan in Shakespeare” in my book Dylan and Shakespeare, in The True Performing Of It Red Planet Books 2019 and 2020.

[iv] There are three printed versions of Hamlet available to us, each markedly divergent from the others. Fascinating though it is to compare them, I am leaving that discussion almost entirely out, given the considerable expansion that covering it would entail.

[v] “We are accustomed to finding multiple layers of meaning in Shakespeare, but modern readers may not realise that most of the plants mentioned by Ophelia were widely known and used in Elizabethan England to induce abortions and control fertility. Lucille Newman, in a paper published in Economic Botany (1979), has suggested that Ophelia’s references to these herbs and flowers should be read as ‘a shocking enumeration of well-known abortifacients and emmenagogues’ which would have been recognised as such by Elizabethan audiences. (An emmenagogue is a drug or agent that increases menstrual flow.) Newman refers to the two-thousand-year tradition of plants used for fertility regulation, including the common herbs rosemary, fennel, rue, pansies, and violets. She gives examples from sixteenth-century herbals where it was said of rosemary, that it ‘bringeth down women’s fleurs’; fennel, ‘it provoketh flowers’; rue, ‘it driveth down floures but it killeth the bryth’; and violet, ‘Seede thereof casteth out conception of women’. Of pansy, as John Gerard (1545–1612) wrote in The Herball or Generall Historie of Plantes (usually referred to as Gerard’s Herbal), its ‘tough and slimie juice’ was used against the pox (syphilis). Dwyer, John “Garden plants and wildflowers in Hamlet”: Australian Garden History , Vol. 24, No. 2 (October/November/December 2012)

Also, see Chelsea Phillips, Kenzie Lynn Bradley, Veshonte Brown, Luke Davis, Kate Fischer, Alycia Gonzalez, and Sarah Stryker, ‘The Dramaturgy of Ophelia’s Bouquet’, Shakespeare 19.1 (2023)

[vi] Microsoft Word - Stilling-Paper-Final-Version (1).docx

[vii] Ibid.

[viii] G.R. Hibbard. Oxford World’s Classics. Reissued 1998.

[ix] The ‘Walsingham tune’ may have been played more than once by Ophelia in her series of songs, as it was in the play I covered in my “Matty Groves” article, Beaumont’s The Knight of the Burning Pestle.

[x] Shakespeare does also seem to write ballads elsewhere, in The Winter’s Tale, for example, but at this distance of time one must always tread with caution in asserting with certainty.

[xi] The use of paradox and ambiguity by both artists are explored at length in my book Dylan and Shakespeare, in The True Performing Of It, Red Planet Books 2019 and 2020.

[xii] Bialo, Caralyn “Popular Performance, the Broadside Ballad, and Ophelia's Madness”,

https://muse.jhu.edu/article/510541/summary

[xiii] This last has similarities to a ballad with a Dylanesque title. “Go from My Window”. It appears in Francis Beaumont’s The Knight of the Burning Pestle, the 1607 (printed 1613) play that included lines from the ballad that began the “Matty Groves” series, “Little Musgrave and Lady Barnard” which I discuss in the Substack post “Our Wells Are Deep”.

[xiv] For Shakespeare and Dylan’s corresponding use of bawdy, see Muir, Andrew: Dylan and Shakespeare, In The True Performing Of It, Red Planet Books 2019 and 2020.

[xv] The later play reminds us of Gertrude’s line “there’s a willow grows askant the brook” and the beautiful verse that follows, describing Ophelia’s death, when we hear Desdemona and Emilia sing “The Willow Song” before they, too, die.

[xvi] Bialo, Caralyn “Popular Performance, the Broadside Ballad, and Ophelia's Madness”, https://muse.jhu.edu/article/510541/summary

Nettie Moore endnotes:

[i] Sean Wilentz (ibid.): “written in 1857 by the blackface performer and lyricist Marshall Pike and James Lord Pierpont, the composer (during that same year) of “Jingle Bells.””

[ii] For more on these topics, see:

(“Nettie Moore”) Robert Reginio, ““Nettie Moore”: Minstrelsy and the Cultural Economy of Race in Bob Dylan’s Late Albums” in Highway 61 Revisited: Bob Dylan’s Road from Minnesota to the World. Colleen Josephine Sheehy, Thomas Swiss, University of Minnesota Press, 2009

(More Generally) Herren, Graley Dreams and Dialogues in Dylan’s "Time Out of Mind" (Anthem Studies in Theatre and Performance) 2021 and Foster & Poe & Dylan - by Graley Herren - Shadow Chasing

(And)

Muir, Andrew Troubadour (2001) esp. chapter on “Love and Theft”, and chapter 6, Dylan and Shakespeare, In The True Performing Of It, Red Planet Books 2019 and 2020.

[iii] Orsino at the opening of Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night.

[iv] Gundersen, Edna DYLAN’S ART IS FOREVER A-CHANGIN’ USA TODAY Posted 8/28/2006 10:36 PM ET.

[v] Jope, Bob, Dylan's Voices: "Nettie Moore" Bob Jope (Publication tba)

[vi] Bob Dylan – Nobel Lecture - NobelPrize.org

[vii] In “American Literature”, from The World of Bob Dylan Cambridge, ed. Sean Latham University Press (6 May 2021).

Thanks for reading More True Performing! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Fantastic work, Andy! Those are some brilliant readings of Ophelia's songs. Along with opening my ears, your writing opens my eyes to connections between Shakespeare and the broadside ballad market. It makes me wonder if some songs in the plays were early examples of what we'd call today "product placement." There was a shilling to be made if Shakespeare ever wanted to put his art in the second best bed with commerce and coordinate with those entrepreneurs hawking their wares inside and outside the Globe. But now I'm thinking like someone from the land of Coca-Cola!

You blew my mind with Part 2--"Nettie Moore" as murder ballad! I missed it entirely, but now I'm totally convinced that you're right. You also make me think that I haven't sufficiently appreciated the importance of Lead Belly as a prototype for the singer-as-killer that Dylan so often channels in his later songs. Great piece, Andy!