1. Our wells are deep

Dylan, Shakespeare and Broadside Ballads

Substack Intro

‘More true performing’ is the name of this Substack, referring to my ongoing exploration of the parallels in Shakespeare and Dylan, especially with regard to broadside ballads. There will be, as can be seen from my first postings, other articles too. I will create sections and tags for them all once I populate the site further. (The tag for the Shakespeare/Dylan ones will be MTP, the tag for other new writing on Dylan will be NDW.)

This one comes with thanks to Bob Jope.

Introduction: ‘Deep wells’ and the interplay between ballads and plays

Douglas Brinkley, in the epilogue to Mixing Up The Medicine,1 tells us that when asked which lyricist he considered a kindred spirit, Dylan replied, ‘Shakespeare…Our wells are deep.’

In the essay that follows, I want to continue my exploration, begun in The True Performing of It, of the parallels in Shakespeare and Dylan with regard to broadside ballads:

“Printing of quarto versions of Shakespeare’s plays took place alongside those of traditional ballads many of which Dylan has sung in one form or another, referenced in his songs and used as the basis for his own work. Furthermore, so popular were these traditional songs that new ones were written, again including a number that Dylan has sung over the years, including ‘The Golden Vanity,’ ‘Barbara Allen’ and ‘The Roving Blade’. The term used for them was ‘broadside ballads’, and this is where the mimeographed magazine in the early Sixties New York folk world got its name. Lyrics and music to topical songs were disseminated in Broadside, with Dylan the star contributor. It would be here that songs like ‘Masters of War’ (see previous article, here) would first appear with the lyrics and music accompanied by small drawings. The language of these Elizabethan ballads had crossed the ocean with the songs and was absorbed into Dylan’s linguistic core as part of the direct link from Elizabethan broadside ballads to the Broadside ballads in the magazine of that name.”2

I am now returning to the subject as it’s so large that it would have been impossible to cover in the original volume, alongside all the other factors examined there. As I mentioned in my introduction to this Substack site, I found myself entangled in a veritable warren of rabbit holes, pleasurably so, but entangled nonetheless. It quickly became clear that it would take another full length book to address my two bards’ balladry properly, or a Substack site. So, let’s get started by noting that in Shakespeare’s time, ballads and plays ruled popular entertainment and were closely interlinked.

There is no need for me to belabour the importance of balladry in the work of Bob Dylan to this audience, but I would like to convey a feeling for how vital they were to Shakespeare and his contemporary playwrights. In that era, the two most popular entertainments were broadsheets and plays, they were intertwined, rather like music and movies in the last sixty years or so, but more so as they were the only two fields at the time. There was as yet no competition from radio, TV, computers or even books. The printing press was getting there, but not there yet in terms of mass publications available to all and the majority of the population were still preliterate.

Plays were multimedia events (visual, dramatic, most times musical, then printed in quartos and, later still, folios) but perhaps more surprisingly, so were broadsheet ballads. Even when presented as woodcuts, most ballads were adorned with illustrations, and these could become more numerous and elaborate when printed. Ballads sometimes also contained the musical score and enterprising hawkers of these songs would often sing them and even partly act out their stories for would-be buyers. In his later plays, Shakespeare becomes more and more involved in examining the links between the forms and their respective claims for satisfying audience tastes and demands.

There was much rivalry, as you would imagine, as they were, after all, chasing the same audiences, but there was also a cross-pollination and support, what would be called in this century’s unappealing term, ‘synergy’. Other than straightforward copying (plays based on a hit ballad; ballads based on a popular play) you find partial lines from plays appear in ballads and you find a great many ballads or quotes from ballads appearing, to a variety of ends, in the theatre of the age.

You have to forget about studying Shakespeare in a book or watching an actor in spotlight on stage in a darkened auditorium and remember that his plays were loud events performed in natural daylight and filled with music and song, including ballads both topical and traditional.

In Shakespeare, you find interwoven lines from, and embedded, ballads playing a myriad of roles. They set scenes; they foreshadow, they give the audience and most actors a breather, or change of emphasis from the ongoing action, they provide an extension to the action and a further exploration, or an explanation even, for the action that has just occurred. Whether quoted fully or partially, they often provide layers of irony. They can also perform multiple functions simultaneously, as they do when sung around the deaths of Ophelia and Desdemona. So central do they become that Shakespeare seems to have written one or more of the ballads in his plays, when he could not locate an existing one that suited his purposes.

Additionally, a strong case can be made, even at the distance in time, for elements of what nowadays we would call ‘product placement’. The ballad sellers in the prime position leading up to the opening doors of the Globe Theatre would be singing from and enacting from the specific ballad they were trying to sell at the time. It would help advertise the play if it featured to some extent in the ballad, and it would greatly boost ballad sales after the play were the song to be sung at a crucial juncture in the play. Such reciprocity between ballads and plays, the implications of their different forms, and how both were born from oral culture but now existed in a world that was turning increasingly to the printed page became ever more prominent themes in Shakespeare’s plays.

Ballads and plays also share subject matter, in particular: infidelity, class boundaries (the normally hidden voices of underclasses), gender issues, the rise and fall of kings and queens, history, supernatural, horror, sensational slayings, femicide and domestic dramas. They could be tragic or comic, serious or silly, and the titles of plays and ballads used the same, what we would call, ‘clickbait’ terms to attract customers. The title “The Lamentable and Tragical History of Titus Andronicus” comes not from the frontispiece to Shakespeare’s, extremely popular in its day, schlock-horror play but from the title of the ballad covering the same tale. The first quarto editions of the play called it “the most lamentable”, which illustrates how close the two forms of popular entertainment were. Both the play and the ballad were first registered in 1594. Debate over which came first has been ongoing for some time with no definitive conclusion as yet agreed. To further complicate matters, there is evidence that they may have been registered on the same day (a printer with an eye for ‘synergy’, perhaps) and that both may have been inspired by an earlier prose version of the tale. However, let us leave that particular set of rabbit holes and head back to the connection between ballads and Shakespeare and then on to Dylan.

Some plays were based on ballads, some ballads retold a play; sometimes, as above, it is difficult to tell which came first. For, even if there is a line from a Shakespeare play in a ballad, you have to resist the automatic conclusion it is taken from the play as you cannot be certain that Shakespeare did not like the line when hearing it in a ballad and then use it himself. Thankfully, there are centuries of research, upon which to draw, in all the areas I have mentioned. I will reference these at the appropriate junctures when we delve into the songs, plays, poems and other writings that Shakespeare and Dylan have given us and the parallels that can be drawn between these.

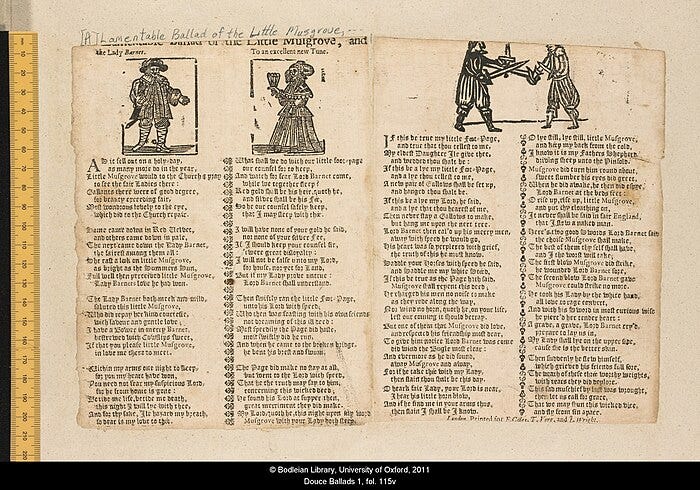

For now, as an illustrative example to set us off on our journey, I will look at a ballad I have never heard Dylan sing and its appearance in a play Shakespeare did not write Instead, this example is chosen due to a coincidence which could have been designed to catch my eye and enchant me. The ballad in question was mentioned in Dylan’s Nobel Lecture in Literature and was quoted on the stage of Shakespeare’s company’s indoor playhouse, the Blackfriars Theatre. Neat coincidence aside, the play, The Knight of the Burning Pestle and its use of the ballad “Little Musgrave and Lady Barnard”, among numerous others, illustrate how interwoven ballads and the theatre were in Shakespeare’s time.

Matty Groves

In that lecture, Dylan tells us that:

By listening to all the early folk artists and singing the songs yourself, you pick up the vernacular. You internalise it. You sing it in the ragtime blues, work songs, Georgia sea shanties, Appalachian ballads and cowboy songs. You hear all the finer points, and you learn the details.

You know what it’s all about. Takin’ the pistol out and puttin’ it back in your pocket. Whippin’ your way through traffic, talkin’ in the dark. You know that Stagger Lee was a bad man and that Frankie was a good girl. You know that Washington is a bourgeois town and you’ve heard the deep-pitched voice of John the Revelator and you saw the Titanic sink in a boggy creek. And you’re pals with the wild Irish rover and the wild colonial boy. You heard the muffled drums and the fifes that played lowly. You’ve seen the lusty Lord Donald stick a knife in his wife, and a lot of your comrades have been wrapped in white linen.

“You’ve seen the lusty Lord Donald stick a knife in his wife” refers to the ballad "Little Musgrave and Lady Barnard" which has, through the years, undergone many name changes in the main characters and its title. For simplicity’s sake, in this article, I will refer to it in modern times as “Matty Groves”, as this is the name by which it has become best known and by “Little Musgrave” when I am talking about the ballad in the time of Shakespeare. (Dylan also refers to the titular character in Tarantula where he writes: “Matty Groves, who secretly at midnight tries to chop down the church steeple.)

The ballad’s narrative is that Lord Donald’s wife instigates and engages in a sexual relationship with Little Musgrave. That sets in motion a chain of events that unfold with a tragic inevitability: the husband's deadly revenge on his wife’s lover, his subsequent offer to his unfaithful spouse to disavow her lover and reconcile with her husband, then his killing of her when she defiantly proclaims her preference for the dead Musgrave. The ballad reflects a prevalent male insecurity surrounding infidelity in a society based on primogeniture, the perceived dangers of women's sexual desires, as well as the love of gossip, particularly around the misdeeds of the nobility.

Dylan will know it through many folk versions, including this one by Joan Baez on a 1962 album: Joan Baez - Matty Groves. This version by Fairport Convention is more traditional, especially with regard to the crucial ending scenes to which Dylan refers: Fairport Convention - Matty Groves.

Lord Donald he jumped up

And loudly he did bawl

He struck his wife right through the heart

And pinned her against the wall

"A grave, a grave," Lord Donald cried

"To put these lovers in

But bury my lady at the top

For she was of noble kin”

The ending, while rather curious to modern ears, highlights the importance of class divisions and social mores in this and other ballads, which is one of their themes Shakespeare exploits most fully on stage, allowing the character in a ballad to express feelings that the character in the play cannot do directly. More of that, later, for now we can note that Lord Donald does everything strictly by the book. He refuses to exercise revenge until his adversary is dressed. He not only gives Musgrave/Matty a sword, but he gives away the better of his two and takes the first blow to himself. He also follows his code of ethics both when killing and burying his wife. We may be attracted to, and feel sorry for, his wife who exercises her sexual agency but she does so in full and deliberate transgressions of codes that her husband is duty bound to obey. This is something she is fully aware of and so she knows the consequences which will follow her answer here:

And then Lord Donald he took his wife

And he sat her upon his knee

Saying, “Who do you like the best of us,

Matty Groves or me?”

And then up spoke his own dear wife,

Never heard to speak so free

“I’d rather a kiss from dead Matty’s lips

Than you or your finery”

Lord Donald’s response is inevitable and his tenacious clinging to his code of honour persists even unto the grave, where his slain wife is buried above her dead lover as she was nobility and he a mere commoner.

"Matty Groves" is a perfect example of traditional ballads that encapsulate timeless themes of love, betrayal, revenge, and the societal constraints and inequalities of its time. Its exploration of gender roles, class dynamics, and the tragic consequences of infidelity continues to resonate down through the centuries. The song links to other ballads of the time and within Dylan’s canon, both performed and written. After looking at those connections, we will trace it back to Shakespeare’s time and theatre.

Although I have no knowledge of Dylan singing “Matty Groves” itself, which makes his decision to highlight it in his speech all the more intriguing, we do have recordings of him, both live and in the studio, playing various related songs and also writing one himself. “Gypsy Davy”/ “Blackjack Davey” parallel “Matty Groves” in featuring noblewomen leaving their wealthy husbands for lower-class lovers . In “Blackjack Davey”, from the Good As I Been To You album, a very similar tale is sung. Dylan - Blackjack Davey

After the ‘boss’ catches up with his straying wife, he again asks her to choose between himself and his wealth and her chosen lover and he, too, gets a disappointing reply:

"Well, I'll forsake my house and home,

And I'll forsake my baby.

I'll forsake my husband, too,

For the love of Black Jack Davey.

Ride off with Black Jack Davey."

"Last night I slept in a feather bed

Between my husband and baby.

Tonight I lay on the river banks

In the arms of Black Jack Davey,

Love my Black Jack Davey."3 [i]

A shortened version of the tale can be found in “Gypsy Davey” which Dylan sang in 1961 and is on the East Orange Tape: Dylan - Gypsy Davey (East Orange Tape).

The wife’s commoner-lover is now a gypsy, as he is in the various “Raggle Taggle Gypsy-o” variants where the boss’s woman is ‘away wi' the raggle taggle gypsy-o’.

From 1961 to sixty-one years later for a Dylan original intertwined with this tradition: Dylan - Tin Angel.

The loping music creates an ominous undertone which emphasises the inevitability of the narrative ending in death. In Dylan’s song the commoner-lover figure is dismissed by the boss as “a gutless ape with a worthless mind.” The runaway wife here shares the same sentiment that all her forbears held, all the way back to Lady Barnard, and declares ‘This man is dearer to me than gold.’ Death all around is the climax to Dylan’s masterful addition to the large folk body of variants on the Little Musgrave tale; with the boss, the adulterous wife who puts love/lust above wealth and stability, nudity and a tragic conclusion all present and correct.

Dylan’s “Tin Angel” additionally references other ballads that played an important part in his artistic development, as noted in his Nobel lecture. The type of ballads, indeed, which also feature in the play that provides us with our first known reference to the ‘Little Musgrave’ ballad. This took place at Blackfriars Theatre, the indoor theatre home of Shakespeare and his company.

Blackfriars and The Knight of the Burning Pestle

The Blackfriars’s Theatre was first set up by James Burbage (father of the famous actor, Richard and impresario for Shakespeare’s company, The Lord Chamberlain’s Men) in 1596, but local residents objected to a theatre in their midst and Shakespeare’s Company did not have the use of it until 1608, the year after The Knight of the Burning Pestle was performed. The period up until 1608 did see the theatre in use for the highly popular children’s companies of the time, these productions and the attendant audiences being deemed acceptable by the local residents.

With Dylanesque resonance, the earliest known reference we have to “Little Musgrave” dates from two 1607 performances of The Knight of the Burning Pestle that challenged the audience and ended in backlash, disappointment and anger. It went on, however, to become popular in later decades and was played to applause in the years leading up to the closure of English theatres. One of the main characters, Mr Merrythought, sings throughout the play, in answer to almost anything said to him. “Little Musgrave” is referenced here:

Mistress. Merrythought: What, Master Merrythought! will you not let's in? what do you think shall become of us?

Merrrythought. [Sings.] What voice is that that calleth at our door?

Mist. Mer. [within.] You know me well enough; I am sure I have not been such a stranger to you.

Mer. [Sings.] And some they whistled, and some they sung,

Hey, down, down!

Ever as the Lord Barnet'a horn blew,

Away, Musgrave, away!4

The ballad must have been well known to the London audience or there would have been no point in these lines being sung. They set the end of the ballad and Lord Donald’s revenge and moral code in the audience’s mind (aka Barnard/Barnet et al) comically deflating the ballad and the play simultaneously and implicitly attacking the tastes of those who like both. Some scholars trace the origins of Matty Groves to Scotland from where it came to North England and then on to the south; others claim the first incarnation was in the north of England and then on through the British Isles.

With a reminder that I am discussing the play and the ballad as one example pair to show how intermingled the two forms were in Shakespeare’s time, I cannot resist highlighting a further coincidental Dylan resonance. That is, audience resistance when it was first performed. The play directly challenged its audience’s expectations and was ahead of its time, resulting in a backlash and subsequent recriminations.

The Knight of the Burning Pestle's failure at the Blackfriars in 1607 appears to have arisen for a variety of reasons, each one given more or less emphasis by different critics.5 Beaumont elected to put on a play seemingly designed for the Inns of Court in a commercial playhouse. The audience composition and expectations were very different in the two venues. It is also claimed that the play challenged the audience's expectation of exercising critical judgment and exhibiting social superiority. The audience at Blackfriars, this theory propounds, revelled in laughing at others but not so much at themselves and they were among the many targets lampooned in this song-saturated comedy.

The play is much in the mode of Cervantes’ Don Quixote, puncturing ideas of chivalry so extolled in ballads celebrating knights of heroic adventures and strict moral codes. The use of ballad excerpts throughout the play provides particularly delicious irony as they highlight the knight’s absurdity. The author’s introduction claims that: Perhaps it will be thought to be of the race of Don Quixote; we both may confidently swear it his elder above a year; and therefore may (by virtue of his birthright) challenge the wall of him. I doubt not but they will meet in their adventures, and I hope the breaking of one staff make them friends; and perhaps they will combine themselves, and travel through the world to seek their adventure. However, as Mandy Rice-Davies once said in very different circumstances: “Well he would, wouldn’t he?”6 To be fair, Don Quixote was not at this point translated into English, and so it may be a fair claim after all. Nonetheless, the novel’s fame was widespread and if not a direct source of the play, the spirit of Don Quixote was very much in the air.

Both “Matty Groves” and Don Quixote have remained popular through the centuries and Dylan namechecks the latter just a few moments later in his 2016 Nobel Lecture in Literature speech quoted above. That continues, from where we left it, with Dylan recounting what the old ballads had taught him and with what he combined it:

I had all the vernacular down. I knew the rhetoric. None of it went over my head – the devices, the techniques, the secrets, the mysteries – and I knew all the deserted roads that it traveled on, too. I could make it all connect and move with the current of the day. When I started writing my own songs, the folk lingo was the only vocabulary that I knew, and I used it.

But I had something else as well. I had principles and sensibilities and an informed view of the world. And I had had that for a while. Learned it all in grammar school. Don Quixote, Ivanhoe, Robinson Crusoe, Gulliver’s Travels, Tale of Two Cities, all the rest – typical grammar school reading that gave you a way of looking at life, an understanding of human nature, and a standard to measure things by. I took all that with me when I started composing lyrics.

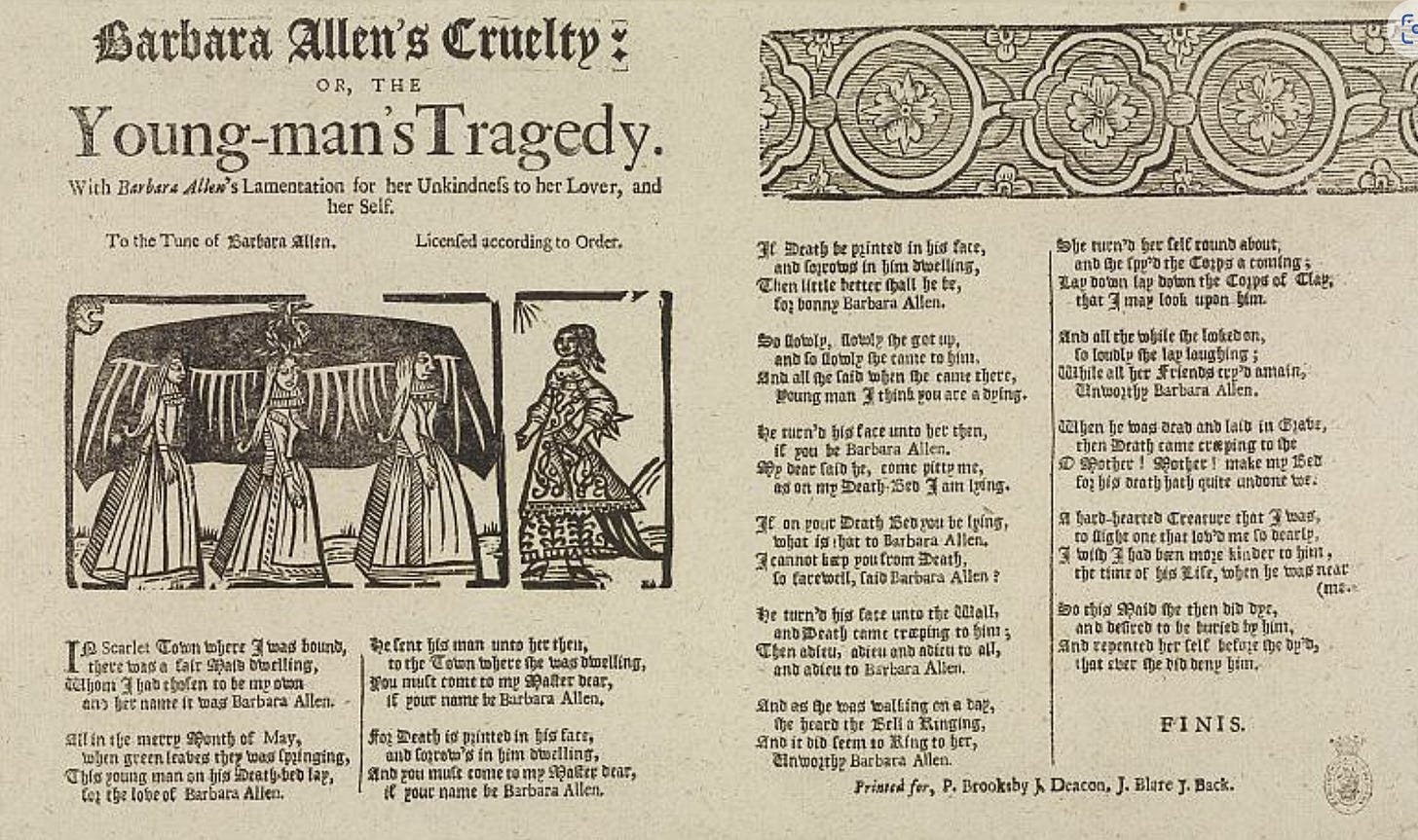

Back on stage at the Blackfriars, Mr Merrythought at least twice quoted from the ballad “Fair Margaret and Sweet William” which intersects both with “Matty Groves” (in many versions some middle-story stanzas are shared) and “Barbara Allen” ( ‘sweet William’ dies in both and the rose-briar motif growing from the lovers’ graves is also duplicated ), which Dylan has sung so memorably on various occasions. and which he also referenced in the aforementioned “Tin Angel” starting immediately, by replicating the opening line of “Barbara Allen”.

Dylan - Barbara Allen (Gaslight 1962)

Dylan - Barbara Allen ( Salt Lake City 13th June 1988) (Noisy crowd, but Dylan soars above it all.)

As already mentioned, there is a recurring theme in many of these ballads of the temptations and dangers of infidelity, especially when it involves a woman leaving her husband for a mysterious lover. Numerous ballads play variants on this as a retelling of the ‘Eve story’, which always leads to a catastrophic ending, the inevitable ‘fall’. One such tale, "The House Carpenter" was an early example of Dylan's education ‘by listening to all the early folk artists and singing the songs yourself’, and from it you can hear him ‘pick up the vernacular’ and ‘internalise it’. Already, he displays vocal mastery control over ballad themes, techniques and motifs.

Bob Dylan - House Carpenter (1961)

Ubiquity of ballads

Ballads have been everywhere in my posts on Substack already. “The Ballad of Donald White” is an example of the extremely popular sub-genre of ‘execution ballads’. Very often these were set to the popular tune of “Fortune my foe” which appears in numerous plays. Execution themselves, often gruesomely enacted, were another major ‘popular entertainment’ along with plays and ballads in Jacobethan times.

A third of Graley Herren’s book was on ‘murder ballads’. As for “Masters of War”, that shows up in the poetic devices. As Dylan said, above, I had all the vernacular down. I knew the rhetoric. None of it went over my head – the devices, the techniques,… “ The rhetorical flourish of anaphora I highlighted in the “Masters of War” article, is present also in “Blowin’ in the Wind” something I compare to Shakespeare’s:

How many make the hour full complete,

How many hours bring about the day.

How many days will finish up the year,

How many years a mortal man may live.

When this is known, then to divide the times:

So many hours must I tend my flock;

So many hours must I take my rest; So many hours must I contemplate;

So many hours must I sport myself;

So many days my ewes have been with young;

So many weeks ere the poor fools will ean;

So many years ere I shall shear the fleece

That was from Henry VI, Part 3, soon after that Shakespeare wrote Richard III (which was what Dylan answered when Christopher Ricks asked what he was reading) and where we can find:

O, cursèd be the hand that made these holes;

Cursèd the heart that had the heart to do it;

Cursèd the blood that let this blood from hence.

“A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall” shares the call and response and anaphoric styling of the ballad it is based on, Lord Randall. “oh where have you been…” “I’ve been to…” .

Just as rhetorical devices are shared in drama and balladry, so ballad themes of adultery, revenge, and the social inequalities and gender dynamics and techniques recur throughout the works of both Dylan and Shakespeare. Much of what I have written of the themes in “Matty Groves” and associated ballads are mirrored in the experience of Othello’s Desdemona, another slain wife and one who tellingly reveals her life story and death via balladry, as does Ophelia when she is driven to madness and suicide in Hamlet. Dylan’s Nobel Laureate speech references "Matty Groves" and similar ballads, highlighting their impact on his artistry, rhetoric and vocabulary. Shakespeare’s artistry, rhetoric and vocabulary were influenced by them, too, and he became increasingly interested in the interplay between the two forms and their respective, perhaps shared, futures as oral cultures entering the age of print.

That is the subject matter for future instalments of ‘more true performing’.

© Andrew Muir, 2025

Endnotes:

Bob Dylan: Mixing Up the Medicine, Eds Davidson/Fischel

Callaway Arts & Entertainment; 1st edition (24 Oct. 2023)

Andrew Muir Bob Dylan & William Shakespeare: The True Performing of It Red Planet (2019 and 2020)

The Knight of the Burning Pestle, 1964: "The Knight of the Burning Pestle," 1964 complete audio recording

For more on this: Why "The Knight of the Burning Pestle" Flopped at Blackfriars in 1607 Author(s): Brent E. Whitted Source: Early Theatre , 2012, Vol. 15, No. 2 (2012), pp. 111-130

Their wells are deep and so is yours, Andy. Thank you for writing and sharing this wonderful and thought-provoking piece. I recently read Shapiro's "Year of Lear" and this is a fantastic chaser. Both show me how little I know, how much further there is to go.

I never really cared for commentary on Bob Dylan, but to let the lyrics speak from themselves. I came across Andy Muir, and he changed my thoughts on that. He is insightful, on target, and I look forward to each new work he offers to those wise enough to read them.