Substack Intro

Ten years ago, I was asked to do a couple of hours a week teaching at a secondary school. This was a new experience for me but it soon grew to be the place I spent most of the working week. My rapid acclimatisation was perhaps aided by a request for me to give a talk to a class whose syllabus included a course on “protest songs of the 1960s”.

I couldn’t help but think back to the 1970s when I was studying the war poets of around half a century earlier in time, from an unimaginable era to my 1970’s mind. This class in front of me were similarly distanced in time from the subject of my talk, Dylan’s “Masters of War”.

The article below follows the course of my talk, which was given with a slideshow projection including various visual backdrops and three audios (1963, 1978 and 1994). Poetic elements were dealt with up front to show I was paying attention to the lesson time being part of a poetry class year and the naming of poetic techniques and their usage is the way to pick up points when work is marked. I broaden the talk out here with additional passages and deeper commentary.

The origins of the song:

We are lucky to have Dylan telling us exactly how the song originated, soon after he wrote it. Dylan was recorded at Alan Lomax’s apartment Manhattan New York City, New York January 1963.[i]: As recounted there:

“This brief session features a young Bob Dylan performing a private performance of Masters Of War followed by a lively conversation about the origins of the song and current geopolitics. Bob Dylan discusses composing Masters of War in England after reading an article about Kennedy and MacMillan. He tells a brief story about Nikita Khrushchev. Mono recording, 8 minutes.”

Dylan recounts for Lomax that he had written the song in London in a ‘rehearsal place out in Putney’. Dylan goes on to recount seeing the English papers ‘putting down MacMillan’ and saying ‘Kennedy's gonna screw him, on these missiles’. Presumably this was all to do with the US’s decision to cancel the Skybolt missile program and the lead up to the President and Prime Minister meeting at Nassau in that December and coming to the agreement that led to the UK purchasing Polaris submarine-launched missiles and maintaining its independent nuclear deterrent.

Dylan continues: “They got headlines in the papers, underneath MacMillan's face, saying "Don't mistrust me, don't mistrust me, how can you treat a poor maiden so?" How surprising, if apt, to have ballad reference to pop up amidst these tense nuclear talks[ii]:

The song, my talk:

I started by playing the Freewheelin’ version and then looking at the grade boosting techniques, the most effective of which is probably anaphora, the use of repetition at the beginning of successive lines. A fine example of this technique can be found in the first verse:

Come you Master of War

You that build all the guns

You that build the death planes

You that build all the bombs

You that hide behind walls

You that hide behind desks

By repeatedly using the words “You that…”, Dylan creates the image that he is speaking directly to these ‘Masters’ as he levels his accusations. At the same time, these lines show Dylan’s deft use of apostrophe, the addressing of absent figures as a powerful means of attacking the people who finance, control and profit from war efforts. The use of ‘me’ and ‘I’, whilst actually referring to the author (Bob Dylan), also implies that he is one of many in the general populace who are opposed to the ‘you’ he is accusing. The name for the technique of implying that the singer is standing for a whole community is synecdoche, and it drives the entire song into a balance of us (against wars) and them (pro-wars). There is no doubt that the intended audience feels when Dylan sing “you hide from my eyes” that these absent, hidden figures are hiding from their eyes, too, and, as with so many, ‘masters’ they have no time for those who ‘speak out of turn’.

You get the idea, and perhaps also a surprise at quite how much poetic technique resides in what is presented as, seemingly, a blunt diatribe. As the talk progressed, I also illustrated similes, rhetorical questions, biblical allusions, plus lists of opposing characteristics and the stanza structure and focus of each verse.

As it was a poetry class, music was only touched upon, though the contrast in each version played was, obviously, dwelt upon later at length. In the beginning, I ran through the background we all know, of Dylan using the Jean Ritchie melody to the old nonsense song “Nottamun Town”. A song whose lyrics would, incidentally, fit nicely on the album, under the red sky[iii]. There was no sign of “Masters of War” pre Dylan’s December 1962 trip to the UK. The various accounts of his performances in December are somewhat contradictory, but most point to it being played to appreciative audiences. Certainly, it was one of the melodies he returned with and to which he had put his own striking words. Jean Ritchie was proud of the melodic contribution made by the Ritchie family in her version of “Nottamun Town” and claims to have pursued a successful financial settlement against Dylan’s uncredited use of same.[iv]

In 1965, Dylan showed his eye for the finest mythic folk traditions when he spoke glowingly of “Nottamun Town” for its lyrics, here he shows his ear for its melody as a perfect fit for his rhetorical oratory and strident denunciations.

The talk went on to look at the twin targets the song takes aim at, its background in history, both general and personal, the controversies it engendered, Dylan’s later revisionist take on its origins and message and seemingly contradictory to this, the repeated reappearance of the song in places and times resonant with war.

I originally posited two targets in the song: conventional war and nuclear war. The song’s depiction of old men sending young men out to die from behind desks evokes nothing so much as the World War 1 poets I mentioned being taught to me at school. Although the song was born into, and implicitly addresses, especially in the fifth stanza, a time of threatened nuclear war, the terminology of “guns” and “bullets” allows a broader range of wars to be covered in the sentiments.

There is no denying the Cold War setting in which it was created, though, and the early 1960’s were a fearful time for Americans. I put in some of this context with a quick sketching of Cuba, the building of shelters and Dylan’s “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall” and “Let Me Die in my Footsteps”.

I also showed them the Duck and Cover film that Dylan would have seen repeatedly in his school days. This was particularly effective given rows of school children were watching rows of school children diving for cover.

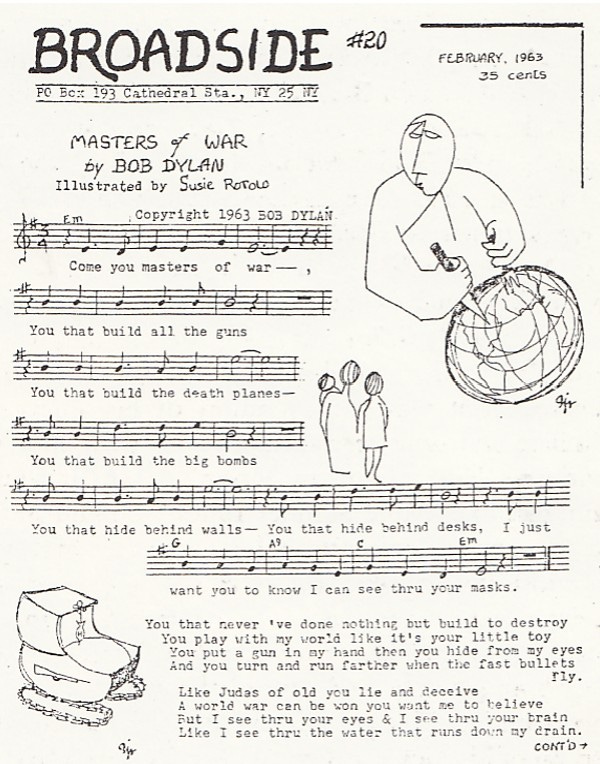

I talked about Suze Rotolo, too, the real one, not the needy and weepy substitute incarnation from A Complete Unknown, and her illustrations for the Broadside lyric publication:

Song Controversies: wishing death and unforgiving Jesus

In the liner notes to The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan, Dylan confronts, in advance, expected criticism of the controversial closing stanza:

And I hope that you die

And your death’ll come soon

I will follow your casket

In the pale afternoon

And I’ll watch while you’re lowered

Down to your deathbed

And I’ll stand o’er your grave

’Til I’m sure that you’re dead

Liner notes: "I've never really written anything like that before. I don't sing songs which hope people will die, but I couldn't help it with this one. The song is a sort of striking out, a reaction to the last straw, a feeling of what can you do?"

I always think, when listening to Dylan’s chastising of his younger self in “My Back Pages” that the line “rip down all hate, I screamed” was inspired by this verse as much as any other. The defence in the liner notes is not a weak one, however, with the extremity of his declaration being fully provoked by the ludicrous, M.A.D. situation he was denouncing. As such, back in ’63 Dylan had no difficulty doubling down on it in concert: Some people say this song I wrote is very naive. But I've got to stand here and really not care, because I do, actually, hope that the masters of war die tomorrow.

The verse has continued to resonate through time, as we shall soon discuss, and has been referred to by other singers. I pointed these out to the class, but thought it politic not to directly quote all of the reference rapper Sage’s Francis’s song, “Hey Bobby”:

"Hey, Bobby...the Masters are back.

They're up to no good just like the old days

They played dead when you stood over their grave, Bobby.

They played dead when you stood over their grave

"Hey, Bobby...them bastards are back.

It's our turn to stand over their grave

I'm a do it right this time...I'm awake...

I'm a wait until their fuckin' skin decays."

For many, another contentious claim in the lyrics was the fifth stanza’s closing couplet, "Even Jesus would never / Forgive what you do", as it stands in contradiction to the doctrinal message of Jesus preaching forgiveness of all sins in others. Much has been written regarding Dylan ‘dropping’ the verse after his ‘born again’ experience. While it is true that he no longer included the verse after 1979, this was not when he ’dropped’ it. It was also omitted from the performances on his 1978 world tour.

The ‘stand over your grave’ verse has, however, resounded around concert halls in many performances over the decades. It still sparks the same rush of cathartic outrage especially in some of the places and times it has featured, as we shall see. Paul Williams, writing of the song in his 1990 book Performing Artist:

“Masters of War" seems to contradict everyone who praises Dylan for the understated quality of his political songs; it shouts, it is openly angry, it points a finger, it even rejects forgiveness and calls for the antagonist's death. I was uncomfortable with it in 1963. But it has weathered very well—unfortunately. The issue is as real today as it ever was: those who consciously and manipulatively participate in war profiteering still hide behind walls and desks and they more than ever encourage and enable the young of faraway nations to slaughter each other.

Critics complained in the Sixties that "Masters of War" was overstated and one-dimensional; today it seems to me we need more Old Testament prophets as brash and angry as young Dylan, who will talk straight and shout in appropriate anger and point some fingers where they need to be pointed, not with smugness or righteousness but with the humility and candor of the speaker in this song. Brashness is sometimes an expression of clarity and courage, and all three are required if we are to break down the "good family man, goes to church, friends in high places" safe houses in which the real mass murderers of our age hide, even from themselves. I still am made uncomfortable by the claim that Jesus wouldn't forgive their deeds, and the line "I hope that you die"—but it is a creative discomfort, that stimulates and forces tough questions. Dylan wrote this one and moved on, as he always moves on, but the songs stay around, and some of them get more relevant as time goes by…”[v]

Nuremberg 1978

Picking up on Paul’s “more relevant” remark, I guided the talk through the decades. The class seemed particularly engaged by the background to, introductory words and performance at Nuremberg in 1978. The stage was built opposite of the podium where Adolf Hitler used to stand during these rallies in the 1930s. The audience, mostly German, therefore were turning their backs to that podium and facing Dylan. The symbolism must have felt close to overwhelming for the man born Robert Zimmerman only thirty-seven years earlier, with the war and Holocaust raging in Europe. According to Wikipedia (yes, I know) “After the concert, Bob Dylan said that it was a very special event for him, which he had marked by appearing in normal street clothes instead of the usual stage clothes.” Your spine tingles at the last sentence with which Dylan introduces the song: “Thank you. That was a new song. This is an old one. Not really new. It gives me great pleasure to sing it in this place!”

Listen here: Bob Dylan live, Masters Of War, Nuremberg 1978

Grammy Awards, 1991

Relevance was exactly the point again at the Grammy Award show in 1991. Here is Greil Marcus looking back that night.

“In 1991, when Dylan was given a Lifetime Achievement Award at the Grammy show, “They now hand these out very promiscuously; at the last Grammy Award show people didn’t even show up for them. But this was unusual at the time; it was a big deal. So here is Dylan being given a Lifetime Achievement Award, and Jack Nicholson comes up and gives a hilarious little speech introducing “Uncle Bobby,” as he puts it. And then Dylan comes on with a very small band. A very noisy, loud, small band, all dressed in dark suits with fedoras pulled down over their heads, looking like characters out of film noir. And they go into the most furious, unrelenting, speeded-up piece of music. And Dylan is slurring his words, you cannot understand what he’s saying, but you don’t need to understand what he’s saying. The sound that’s being made is so exciting, so thrilling. And about halfway through, at least for me—other people might have caught on more quickly, maybe later—I realized he was singing “Masters of War.” His most unforgiving, bitter, unlimited denunciation that he’s ever recorded. It’s a song about arms merchants. It ends with “And I hope that you die, I’ll stand over your grave, I’ll follow your coffin (sic)” Not too many songs really wish for the death of the subject, the person who’s being addressed.” [vi]

Listen here: "Masters Of War" - Live At The Grammy's 1991

My own memories are to be found in my book on Dylan’s ‘Never Ending Tour’:

“Dylan performed his damning anti-war indictment, “Masters Of War”, a brave choice given that the Gulf War was still going on and hawkish jingoism was rife. However, since he chose to sing it without a pause for breath, no-one who did not already know the song would have got the message. In fact, many who did know the song didn’t even recognise it here. Not only did Dylan’s nasal passages sound blocked (he later revealed he’d had a cold) but it seemed he had swallowed a burst of helium before starting to sing. Many observers thought he was singing in Hebrew. The tuxedoed crowd looked on in utter bewilderment. The next day’s papers marvelled how only Dylan had performed a song with any meaning and purpose, but then, being Dylan, he had made it completely incomprehensible. So far this was all quite funny, but pure comic genius was still to come in the form of his acceptance speech, as we will see in a moment.

The event worked a treat, Dylan acting so shockingly dissimilar to the norm for TV award ceremonies: newspaper after newspaper carried the story along the lines of, “Want to know what Bob Dylan was singing last night, it was.....”, then acres of print about Dylan, about the war, about the Grammies. Most comment was pretty favourable too, praising Dylan for being an individual, for resisting the cloying show business approach and for still, all these years later, being a rock’n’roller who made you think.” [vii]

This one I did not play for the class. From memory I quoted the “swallowed a burst of helium before starting to sing” comment which inevitably led to a chorus of requests for it to be played. I decided discretion was the better part of valour here, as I thought it would ruin the atmosphere required for the next segment, Hiroshima in 1994.

You would think that the point of Dylan choosing this particular song to sing at that time was too obvious to need to be spelt out, but, as Greil Marcus continued form his previous quote: “Then he was asked later, later that night, why he chose to sing that song. This was 1991. It was February, it was the middle of the bombing of Baghdad, the first American-Iraqi war. And the Grammy show was kind of a respite from the round-the-clock coverage of that magical pinpoint bombing and all that green film. And he said “Well, why did I perform that song?” He said, “The war.”[viii]

Hiroshima, 1994

Listen here: Hiroshima, 1994

The greatest surprise of the Japanese 1994 dates was saved for February 16th, when a reworked acoustic “Master of War” was performed in Hiroshima. This was the first acoustic performance of the song since 1963. An apt, if harrowing, choice, it was given a breathtaking performance. Dylan once again sounded like an angry young man: the folk singer rebelling with cause after cause. Here he was in Hiroshima, an American in the first Japanese city obliterated when the U.S. dropped The Bomb, singing out against the terrible sufferings of the innocent in war. I have rarely been as moved. How strange that such a blunt, unforgiving, adolescent piece should achieve that effect. Or rather how strange it would have been in almost any other location.[ix]

My fanzine of the time was winding up, but contributor Robert Forryan should still have been aware that accepting unsolicited tapes from an editor was akin to escorting a large wooden horse into Troy. There was still a final subscriber’s special to go and he duly ended up in it, writing on the first acoustic performance of “Masters of War” since thirty-one years earlier. Robert’s article is now another thirty-one years in the past . Out of the sixty-two year span, the first half seems so much longer in my mind than the second. In his article, Robert even mentions the anguish he feels at how long it has been since he first knew the song. I hope this Substack piece of mine does not redouble that ‘anguish’. Back then, Robert wrote:

“The conclusion to be drawn, then, is that there is no kinder act that one Dylan fan can perform for another than to send him/her a wonderful, but unsolicited, tape. It is just that unexpected tape that stuns, that claws at your innards, that knocks you sideways and recreates those emotions that you felt that very first time you really heard Dylan. Such an act of kindness has been something I have known several times, thanks mainly to Andrew Muir. It was just such an act of his that spawned this article. This was the arrival, in April 1994, of a tape of the Hiroshima show of 16 February of that year. It wasn't the whole tape that I responded to, good though it is, but the first track that I heard. This was not the opening song, Jokerman, but the song that Andrew had contrived that I hear first. So remarkable did he consider the performance of this song to be, he had wound the tape to the exact point that would ensure that this was the song I first heard.

Nothing could have been better designed to induce a positive response in this listener. Had he written a long letter extolling the merits of this one performance of this particular song I could only have been disappointed. By doing it this way, and by not telling me that this is what he had done, Andrew virtually guaranteed that he achieved the desired effect. Within seconds of rolling that tape, I was stoned on Dylan; out of my mind on just one song. The song, and the inspiration for me to be writing now, was Masters Of War - according to The Telegraph the first acoustic version of Masters since 1963. Since Hiroshima, of course, Masters Of War has become a regular choice in Dylan's acoustic sets and featured strongly during the 1995 European Tour; but at the time this acoustic performance was a revelation.

A gentle, haunting, melodic instrumentation; not at all angry, this time, and a voice from which the years have dropped away. This is the voice of a young man. It sounds as if for one night, and for one song, Dylan has done a deal with the Devil. ‘Let me have my youth back for this song in this place – let me be inspired.’ A pact with the Devil – or maybe a prayer to the Lord.”[x]

Greil Marcus continued, in 2005, from the last piece quoted above, by saying: “One of the most striking performances of that song that I’ve heard was on election night. I think it was in Des Moines, Iowa. It was on election night, when all the votes had been cast, but the results were not yet known. It’s a song that the world will not let wear out.”

New Century; same old relevance

Yes, the song’s relevance continued, the world will not let it wear out: new century but same old human race, mass murders and another Gulf War. After the next President Bush’s speech proclaiming “we must send more troops there” of “Masters of War” sounded like a pointed rendition, that night, especially as it was followed by “It’s Alright, Ma” with its famous line ‘even the President of the United States must have to stand naked.” Coincidence? Possibly, possibly not, before that Dylan had come out with comments on “Masters of War” that surprised us all.

In 2001, Dylan came out with a startling piece of seeming revisionism on “Masters of War”, telling Edna Gundersen in an interview published in the USA Today, on September the 10th, (a chilling date for such a topic as ours here, with unspeakable horror a mere day away) that “It’s not an anti-war song. It's speaking against what Eisenhower was calling a military industrial complex as he was making his exit from the presidency. That spirit was in the air, and I picked it up."

It was a time of interviews, with “Love and Theft” being released on the same say as the Twin Tower attacks. The L.A. Times, on September the 16th, saw this theme expanded "Every time I sing it someone writes that it's an antiwar song. But there's no antiwar sentiment in that song. I'm not a pacifist. I don't think I've ever been one. If you look closely at the song, it's about what Eisenhower was saying about the dangers of the military-industrial complex in this country. I believe strongly in everyone's right to defend themselves by every means necessary".

Given what we have seen regarding the origins and history of the song so far, these seem surprising claims. Dylan is vehemently denying it is an anti-war song, and claims he is not a pacifist and he ‘thinks he never has been’. There is an interesting shift away from certainty there regarding the past. Perhaps he is thinking back to when he wrote the song, when he was with Suze Rotolo and very much appeared to be a pacifist to all who knew him at that time. That was then, however, and now was now with Suze and her CORE activism a distant memory.

Certainly, Dylan was never a politically engaged pacifist in the way his then girlfriend Suze Rotolo and soon to be girlfriend Joan Baez were. What Dylan was enraged about, the money making and controlling ‘military-industrial complex” - note the figure eating the world in Suze’s illustrations for Broadside - was, as Dylan correctly notes, a danger made clear by President Eisenhower as he handed over to the doomed JFK with these words of warning about the dangers of the military industrial complex in a farewell address in February, 1961. It is worth reproducing in full as it was a mighty message, though alas it was a warning that went unheeded by most:

“A vital element in keeping the peace is our military establishment. Our arms must be mighty, ready for instant action, so that no potential aggressor may be tempted to risk his own destruction. Our military organization today bears little relation to that known by any of my predecessors in peacetime, or indeed by the fighting men of World War II or Korea.

Until the latest of our world conflicts, the United States had no armaments industry. American makers of plowshares could, with time and as required, make swords as well. But now we can no longer risk emergency improvisation of national defense; we have been compelled to create a permanent armaments industry of vast proportions. Added to this, three and a half million men and women are directly engaged in the defence establishment. We annually spend on military security more than the net income of all United States corporations.

This conjunction of an immense military establishment and a large arms industry is new in the American experience. The total influence -- economic, political, even spiritual -- is felt in every city, every State house, every office of the Federal government. We recognize the imperative need for this development. Yet we must not fail to comprehend its grave implications. Our toil, resources and livelihood are all involved; so is the very structure of our society.

In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex. The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist.

We must never let the weight of this combination endanger our liberties or democratic processes. We should take nothing for granted. Only an alert and knowledgeable citizenry can compel the proper meshing of the huge industrial and military machinery of defence with our peaceful methods and goals, so that security and liberty may prosper together.”

US Airforce man, Doug Mackenzie, had an exchange with Dylan that reveals a Dylan lauding those who ‘put themselves in harm’s way for their fellow countrymen’ while his son, “Masters of War” is still a rallying cry for opposition to the military-industrial ogre they serve and which Eisenhower so clearly foresaw. [xi]

***

Substack Outro

My talk at the school ended with the Doug McKenzie exchange. I thought at first that I would expand on it for here, by maybe going back and linking this postcard exchange to Dylan playing the song at West Point military academy in 1990. A head-spinner that no-one from the original listeners would have credited as being possible. Even in trying to imagine it, you would portray in your mind’s eye, a Dylan as avenging prophet speaking truth to power and yet the circulating recording of that momentous sounding event conveys nothing out of the ordinary, nothing particularly different to “Masters of War” on other nights of the tour. I thought, too, of later performances and started to Google search links for these when all such plans came to an abrupt halt.

To badly misquote: ‘Ain’t it just like the ‘Net to play tricks on you’. When I searched for performances over the last couple of decades, I found plenty, but I also found this webpage: Bob Dylan's Masters of War, by Michael Organ, providing a lengthy look at “Masters of War” through time. I could hardly believe it. Ah well, there’s another take on the origin and evolution of this song, for you, plus numerous links to live performance through the decades.

***

© Andrew Muir, 2025

[i] Released on Various Artists - Root Hog Or Die: 100 Years, 100 Hundred Songs, An Alan Lomax Centennial Tribute, 6LPs,Mississippi Records MRP060LP, 12 February 2016.

(Burl Ives.)

[iii] The original release had no initial caps in the album title (but did on the title track.)

[iv] Clinton Heylin, Revolution in the Air: The Songs of Bob Dylan, 1957-1973 Chicago Free Press, 2009 pp 116-7 for more background to this.

[v] Paul Williams: Bob Dylan Performing Artist Book One, Xanadu, UK 1991 page 76.

[vi] Greil Marcus and Don Delillo discuss Bob Dylan and Bucky Wunderlick (2005) | GreilMarcus.net

[vii] One More Night: Bob Dylan's Never Ending Tour CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform; (26 July 2013)

[viii] Greil Marcus and Don Delillo discuss Bob Dylan and Bucky Wunderlick (2005) | GreilMarcus.net

[ix] One More Night: Bob Dylan's Never Ending Tour CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform; (26 July 2013)

[x] Hts_ssx.pdf Follow the contents page to find Robert’s article.

[xi] The site which provided this image, positively-bobdylan.com, is currently showing “discontinued”.

A fine piece, Andrew. Thank you. Reminded me of the granular analysis in your excellent book, Razor’s Edge, chronicling your devoted following of the NET. (I devoured it in two sittings, btw).

Great piece! Dylan often offers a very conspiratorial view of things only to deny or obscure later. There’s a lot of that in his ‘80s interviews I think. Did you ever write about Neighbourhood Bully at all?