Substack Intro (Happy “Isis Day” everyone! )

Here is another chapter in my series “More True Performing”, this one explores the history of the oral tradition of wandering entertainers from the sixteenth century and points to parallels with hobo-minstrels like Woody Guthrie and Lead Belly. It also examines the differences between traditional and street ballads in Shakespeare’s time, and how this is mirrored in the divergent strands traditional ballads and ‘protest songs’ in the 1960s.

Voices of the People

Shakespeare and his acting company evolved out of the traditional travelling troupes of actors known as “travelling players”. The original legal status of these wandering men was akin to that of vagrants. The same applies to the original balladmongers and minstrels. All groups were looked down upon by the better off in society and were little more than outcasts with an ability to entertain and experience in doing so. In time, with the advent of permanent theatres in London, added to the protection via the patronage of nobility or royalty (such as Shakespeare’s “The Lord Chamberlain’s Men” and then “The King’s Men”), later acting companies could gain some social standing and security, but the earlier social stigma still lingered heavily. Those without such noble patronage were still in the same bracket as balladmongers and wandering minstrels. This shared heritage further solidifies the many connections I have been highlighting between the theatre and ballad spheres. The split that then occurred between commercial, professional enterprises and those who remained within the folk, amateur community, foreshadows a similar fork in the road for Dylan, centuries later.

Minstrels

The figure of the minstrel has evolved over time, carrying a range of associations that shift with each era. Aptly for my study of Shakespeare and Dylan as parallel bards from different centuries, the term "bardic", especially in Scotland, in Shakespeare’s time meant “hobo-minstrel”, a wandering entertainer living on the fringes of society.

The role of minstrels evolved with, and developed into, the rise of ballad writers and sellers, and as travelling theatrical troupes with musical "interludes" gave way to professional acting companies the minstrelsy began to fade. Yet, wandering minstrels are the beginning of our story; musical entertainers, often of a very low social status and lacking formal training, they were primarily singers, yet were not confined to music alone: instead, collaboration across different forms of entertainment was common.

Minstrelsy was deeply embedded in the oral culture from which both traditional ballads and Shakespearean drama emerged. Ballads were often sung by minstrels, and the performance of plays, similarly reliant on performers' voices, featured minstrels singing interludes and performing the jig or “merry dance” that brought proceedings to a close. This practice carried over into the Elizabethan era, underscoring how closely intertwined oral tradition and dramatic performance remained.

Even the word "ballad" itself points to this connection: "ballad" is derived from the Latin word "ballara”, meaning “dance"[i]. This connection to musical performance and movement survives all the way through to Bob Dylan. I recall, as a schoolchild in Scotland, being made to dance to the tune of "The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll" for an end-of-year show and then some years later hearing that traditional dance melody repurposed by Dylan to such haunting effect. I could still hear the teacher counting us in "one, two… three, four" as the final notes to Dylan’s masterpiece faded out. The epic ballad “Tempest” takes us from an individual to a communal tragedy and conveys its grim litany of the dead to another melody which echoes sad waltzes from times past. “Ballara” and its subsequently derived terms illustrate the interconnections of song and dance down through the centuries. Theatre companies, such as Shakespeare’s, employed ballad makers to write the jigs that were performed after the performances ended as well as any interludes deemed necessary during the dramas presented.

Prior to that, minstrels provided the interludes and post-acting “merry dances” as well as widely disseminating ballads and presumably improvising and perhaps creating new ones as they wound their weary and perilous roads around the countryside. Over time, "minstrel" came increasingly to denote musical entertainers of the lowest status. Their lack of formal training became an issue, and in time they became differentiated from professional players. Initially, all the entertainers mentioned here were amateur and wandering types: hobos, tramps and vagrants as far as the law was concerned.

As ballad selling developed as a trade, with hawkers singing the wares they were selling, there was an inevitable overlap with the repertoire of minstrels, whose songs were also now increasingly circulated as broadsides. With the rise of ballad sellers and professional players (actors) the role of the minstrel gradually diminishes into the past. Alongside the growing professionalism and commercialism of acting companies, there was also a continuation and development of musical performances at court, aristocratic houses and universities. These performances were more respectable than the strolling players in market places and they also fed into the commercial theatre of the 16th century. However, it is worth remembering that the origins of professional acting and the theatrical interlude are deeply rooted in the traditions of minstrelsy.

Balladmongers, Ballad Hawkers, and the Act of 1572

The development of ballad culture in the early modern period cannot be fully understood without considering the crucial role of balladmongers and ballad hawkers. As the popularity of printed broadsides grew, ballad-selling emerged as a distinct trade, overlapping with but also diverging from the older minstrel tradition.

Ballad hawkers, or balladmongers, were individuals who sold broadside ballads to the public (“monger” means “trader”, as in “fishmonger”). While both terms relate to the selling of ballads, "balladmonger" can also mean a composer, though this brought with it the connotation that these songs were of low standard and eminently disposable. Terms that many, including rock and folk fans, have used to describe “pop music”.

With the advent of affordable printing technologies, ballad sellers became central to the dissemination of popular songs. They travelled extensively, moving between towns and rural communities, selling not only ballads but also a variety of easily portable goods. To attract customers, they would frequently perform the ballads themselves, singing or even partly acting out the dramatic narratives. Much like minstrels and early theatrical troupes, these sellers occupied a precarious social position. They lived on the margins of society, often without fixed residences, guild affiliations, or legal protections. Nevertheless, balladmongers were vital agents in the cultural economy of their time, maintaining wide-ranging trade networks and a nuanced knowledge of local tastes. Their primary product, the broadside ballad, enjoyed widespread popularity throughout all levels of society, and there is even evidence of schoolchildren, (privileged males only, at the time), being “caught in possession” of copies.

Caralyn Bialo notes that: “Although the London playing companies were officially distinguished from minstrels and ballad sellers under the 1572 ‘Acte for the Punishment of Vacabondes,’ the status of professional players continued to be contested in part because of the cultural associations among actors, minstrels, and vagrancy.” The antitheatrical writer Stephen Gosson, for example, accused players of having "bene eyther men of occupations, which they have forsaken to lyve by playing, or common minstrels".

Sadly, human nature being what it is, those in the second lowest rung are often those most cruel to those at the very bottom. A documentary I saw recently recounted testimony from British ex-patriates in apartheid South Africa saying that when the “lowest of the low” later came over from the UK, they delighted in having an underclass to persecute and torment. They exulted in no longer being the bottom rung, but in having a level beneath them. In turn, this brings to mind Dylan singing in “Only A Pawn In Their Game”:

A South politician preaches to the poor white man

“You got more than the blacks, don’t complain.

You’re better than them, you been born with white skin,” they explain.

That 1572 Act, slight elevation though it was, effectively moved actors in settled companies, with noble patronage, up a level from their old counterparts in travelling, oral culture. So we find, in 1589, that Thomas Nashe, sometime playwright and man of letters, felt that the theatre was by now elevated enough to join in the attacks on balladmongers. Caralyn Bialo writes that:

“Henry Chettle and William Harrison both asserted that "masterless men" used the pretense of minstrelsy and ballad selling to avoid real work. 'Many of the educated elite linked the ballad's literary inferiority directly to the base status of the ballad seller and ballad writer. Thomas Nashe attacks the "stitcher, weaver, spendthrift or fiddler [who] hath shuffled or slubberd up a few ragged rimes."" For Nashe, hack writers and bumbling, vulgar musicians emblematize the genre's coarseness.”[ii]

To be fair, broadsheets were often merely ephemeral, lacking sophistication or artistry but they were not always so and it is somewhat galling to read Nashe’s hyperbolic put-down.

You could counter by reminding me that although Dylan turned his back on his protest songs in very strong language, too, and went on to explore deeper layers of society and human nature from 1964 onwards, he was back with a blunt protest song in 1971, with a “street ballad”, if ever there was one, in “George Jackson”. Then, five years later, “Hurricane” opened Desire and went on to play a central role in the Renaldo and Clara movie.

What I am highlighting, overall is that snobbery against song is a constant through the centuries. One is reminded of Robert Louis Stevenson, decrying Rabbie Burns for spending his time on traditional Scottish songs rather than in writing “real poetry”. Such dismissal of song as opposed to “real poetry” has robbed generations of audiences from enjoying much, if not most, of the many musical elements that are integral parts of Shakespearean drama. It is part of the centuries long elevation of page over stage. Dylan and Shakespeare are masters of both print and performance, but if you were to weigh the balance of study and commentary between the two forms of expression, then you would have a pair of scales very heavily weighted to the former.

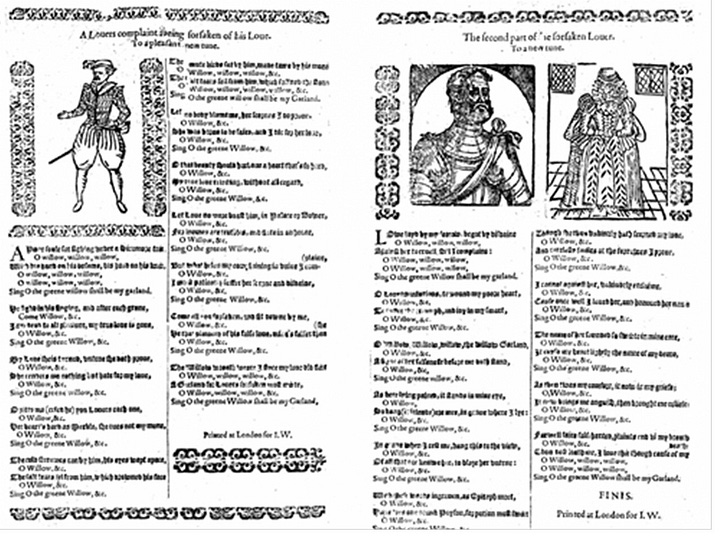

Broadside Ballads and the Rise of Print Culture

The broadside ballad was a song printed on a single sheet of paper, designed for mass appeal, particularly among the less affluent classes. In a period when books were expensive and inaccessible to much of the population, broadsides became a crucial medium for entertainment, moral instruction, news, and social commentary. Above all, they were the perfect vehicle for songs, adorned with a catchy title and occasionally a woodcut illustration; these ballads narrated stories in verse form and were intended to be sung to well-known tunes. These tunes could travel from song to song, or new melodies written for existing narrative verses.

Many broadside ballads centred on themes of love: love won and love lost, “pop songs” of their day, you might say. These ballads often reflected contemporary attitudes towards women, marriage, social and sex mores. Broadside printing was not limited to ballads, instead it was impressively extensive and encompassed a variety of topical content, be that news, salacious gossip and stories of the powerful. There was even the phenomenon of flyting - something akin to early flame wars on social media, showing how innate is our propensity to use wonderful new inventions for trivial and debased purposes – where insults between ‘celebrities’ of the day were eagerly followed as they flew back and forth. We are concerned, here, however with their star item the broadside ballad.

The rise of the broadside not only altered the circulation of ballads but also shifted perceptions of oral and written culture. Minstrels, once central to the oral transmission of ballads, increasingly came to symbolize the historical and folkloric origins of songs that were now being printed and archived. This was not a simple replacement of oral by written tradition, but rather a complex evolution of roles within a rapidly changing media environment. Ballads and Shakespeare’s plays shared the communal aspects of traditional life; they were created to be sung in the streets and taverns, or staged in market places and theatres.

Hittin’ some hard travelin’ too

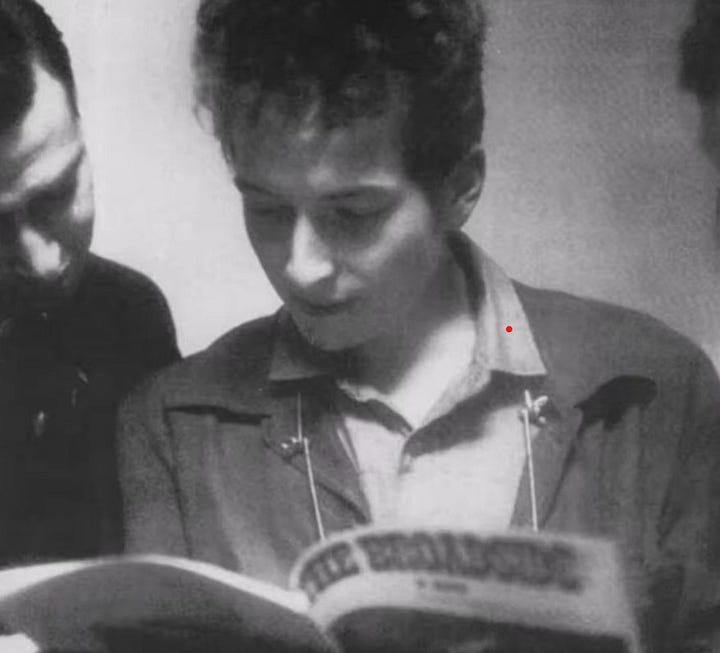

Bob Dylan arrived in New York as a self-styled hobo minstrel with exaggerated tales of an itinerant backstory. He did, however, travel round and sing, albeit to a lesser extent than he claimed and he idolised Woody Guthrie and his friends and companion inheritors of the century old tradition of wandering minstrels and balladeers:

“Here’s to Cisco an’ Sonny an’ Leadbelly too

An’ to all the good people that traveled with you

Here’s to the hearts and the hands of the men

That come with the dust and are gone with the wind”[iii]

Song To Woody

In a similar manner to how the invention of the printing press and the growth of printing changed everything for the old minstrels, so too did the advent and growth of phonograph recordings prove a key factor in the story of Bob Dylan and other singers of last century. When still in the roving minstrel state, the ballads of these folk musicians could and would evolve within oral singing traditions and be tweaked to current events and even passing fancies of the performers themselves.

Just as print culture reshaped the transmission and perception of popular song, without fully displacing oral traditions, so, to varying degrees, recorded versions and “official lyrics” sometimes transformed the previously fluid folk material of the twentieth century of “official lyrics” in copyrighted form. The tension between ever evolving live music and the fixed nature of studio recordings and printed lyrics is a central theme of Dylan’s career and Dylan scholarship.

Dylan’s emergence as a leading artistic figure of the second half of last century surprisingly and spectacularly reversed the emphasis back from printed to oral culture. Shakespeare and Dylan as writers for performance, primarily for the stage not the page, but with their dual roles as writers of the highest literary worth, are at the centre of these conflicting movements and forces and both were highly aware of their position at the cultural nexus of their respective eras.

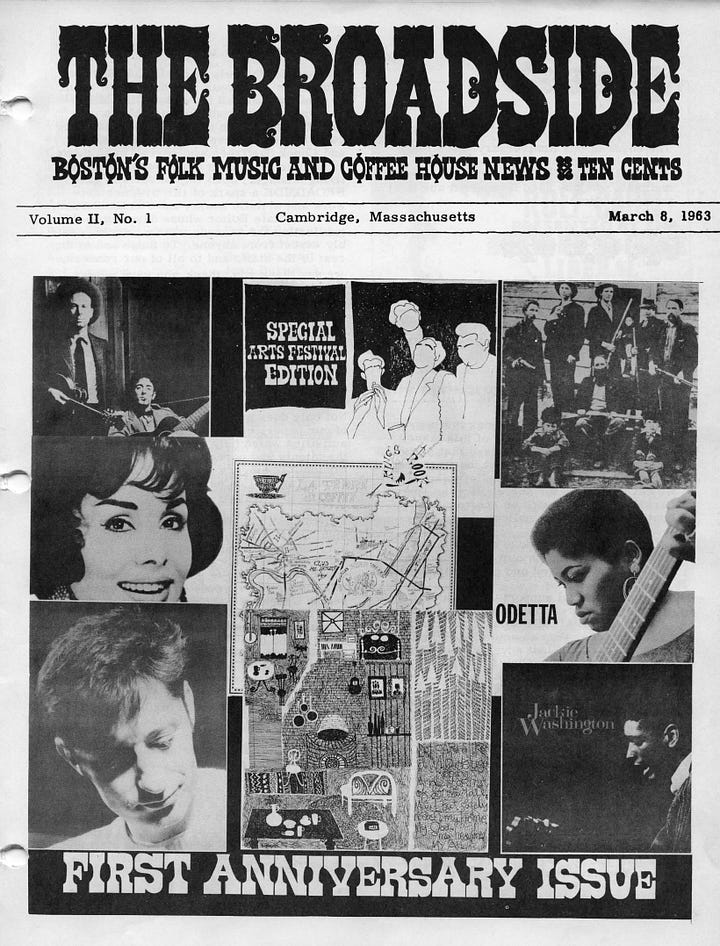

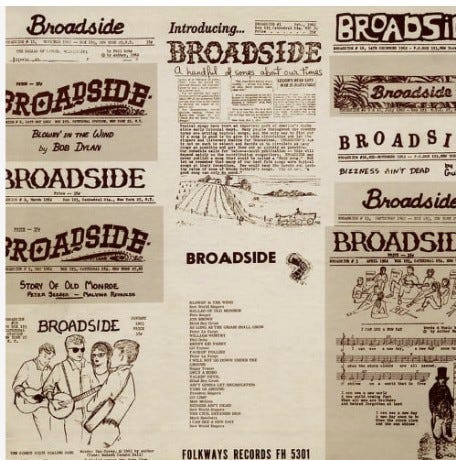

Further strong parallels between the two bards appear in the dual nature of ballads both in the 1590s and 1960s. This is seen in the differences between traditional and broadside ballads back in the day, and traditional ballads and protest songs for Broadside magazine at the start of Dylan’s career.

Traditional Ballads and Broadside Ballads

The term "ballad" itself encompasses a range of meanings. Broadly, it refers to a narrative song composed in a stanzaic form suitable for singing, dealing with themes such as love, tragedy, crime, or historical events. However, scholars distinguish between "traditional" or "popular" ballads and "broadside" or "street" ballads, based on their origins and modes of transmission.

Traditional ballads are typically of anonymous authorship, transmitted orally across generations, and subject to variation in the act of performance. They are often associated with rural settings and exhibit distinctive structural and stylistic features shaped by communal memory and improvisation. In contrast, broadside ballads were generally the product of semi-professional or "hack" writers, aimed at a predominantly urban audience. Unlike traditional ballads, broadsides existed as tangible documents: cheap, printed artifacts designed to exploit the commercial possibilities of the burgeoning mass media. It should be noted that the boundary between the two was often fluid. Some traditional ballads were adapted, edited, and printed as broadsides to achieve greater commercial success, while others persisted in oral circulation even after being committed to print.

At the time Shakespeare started to write plays, street ballads, which he often included or alluded to in his plays, were, amongst other things, the protest songs of his day. Like Dylan’s early “protest songs” these “street ballads” were topical and often expressed deeply felt resentment against social injustices. They were more city based than the traditional, rural repertoire and written, as their name suggests, in the colloquial language of the street.

There are many similarities between this and Bob Dylan’s emergence in the Greenwich Village scene in the early 1960s. Again there is a split between traditional folk music and the songs Dylan and others wrote for their version of the broadside ballads, the magazine, “Broadside”. Dylan, as we all know quickly became the “prince of protest”, churning out anthems, laments and witty put downs all decrying the political and societal injustices of the day. He was to turn against this, castigating himself for turning newspaper stories or headlines into instant songs and questioning his motives for so doing. As he tried to shake off this image he had so successfully created, (it was so strong that it persists in the general public’s view of Dylan to this day), his waspish tongue turned against his previous creations in interviews. However, Dylan carefully distinguished between his “street ballads” and traditional ones. He explained this in 1966:

“And folk music is a word I can’t use. Folk music is a bunch of fat people. I have to think of all this as traditional music. Traditional music is based on hexagrams. It comes about from legends, bibles, plagues, and it revolves around vegetables and death.”[iv]

In the interview he is defending himself from accusations that he had “killed folk music”, and continued:

“There’s nobody that’s going to kill traditional music. All these songs about roses growing out of peoples brains and lovers who are really geese and swans that turn into angels -they’re not going to die. It’s all those paranoid people who think that someone’s going to come and take away their toilet paper – they’re going to die. Songs like “Which Side Are You On?” and “I Love You, Porgy” – they’re not folk music songs…”

Noting that in traditional music “mystery is a fact, a traditional fact”, Dylan goes on to say:

“I listen to the old ballads. I could give you descriptive detail of what they do to me, but some people would probably think that my imagination had gone mad. It strikes me funny that people actually have the gall to think that I have some kind of fantastic imagination...”

Dylan uses the term “folk singer”, in this interview, to denote protest singer of contemporary street ballads. He sets this up in opposition to the “purity” of traditional ballads, Dylan again stressing that the “old”, the traditional, cannot be killed, because it is full of mystery: a mystery containing magic and wonder, death and holiness:

“…traditional music is too unreal to die. It doesn’t need to be protected. Nobody’s going to hurt it. In that music is the only true, valid death you can feel today off a record player. But like anything else in great demand, people try to own it. It has to do with a purity thing. I think it’s meaninglessness is holy. Everybody knows that I’m not a folk singer.”

I have written, both in this series of articles and elsewhere, of Dylan and Shakespeare’s “gappiness” (to again use Emma Smith’s term) as a strength in their writing; coupled with the marvellous way they make us ask pertinent questions, rather than provide pat answers, it provokes a sense of wonder and, to use Dylan’s term on traditional ballads, mystery. When this is all allied to their figurative and symbolic language, the listener/reader is transported into speculative and endlessly fulfilling realms. Realms where one is always satisfied, but never sated; instead always led on to further exploration and delight.

Substack Outro

In both senses of the word, Bob Dylan is a balladmonger par excellence, and you probably have never thought of Shakespeare being called the same, but a leading critic, Tiffany Stern has written: “...the word ‘balladmonger’ in the period sometimes indicated a ballad seller and sometimes ballad- writer, Shakespeare emerges as at least one form of balladmonger, and perhaps both.”[v] I hope that quote piques your interest in the next stage in this series: “Leveraging the Synergies, 16th and 17th century-style”, plus Shakespeare’s staging of a balladmonger in action and all the parallels with Dylan’s art and achievements.

©Andrew Muir, 2025 With thanks to Rowland Wymer.

[i] The word comes into English via the French “ballade” popularised in the dancing tradition of the “Provencal ballade”.

[ii] Bialo, Caralyn. “Popular Performance, the Broadside Ballad, and Ophelia's Madness” Studies in English Literature, 1500 - 1900; Baltimore Vol. 53, Issue 2, (Spring 2013): 293-309.

[iii] Song to Woody | The Official Bob Dylan Site .

[iv] Hentoff, Nat. Playboy Interview, March 1966 , New York City, New York The Fiddler Now Upspoke.

[v] Stern, Tiffany. "Shakespeare the Balladmonger?" Rethinking Theatrical Documents in Shakespeare’s England. Ed. Tiffany Stern. London: The Arden Shakespeare, 2020. 216–238.

Bibliography:

Bialo, Caralyn. “Popular Performance, the Broadside Ballad, and Ophelia's Madness”Studies in English Literature, 1500 - 1900; Baltimore Vol. 53, Issue 2, (Spring 2013): 293-309.

Chess, Simone. Shakespeare’s Plays and Broadside Ballads,” Literature Compass (volume 7, 2010). pp. 772-785.

Nebeker, Eric. “The Broadside Ballad and Textual Publics”, Studies in English Literature, 1500-1900 , Vol. 51, No. 1, The English Renaissance (Winter 2011), pp. 1-19. Rice University.

Sewell, Helen. “Shakespeare and the Ballad: A Classification of the Ballads Used by Shakespeare and Instances of Their Occurrence” Midwest Folklore , Vol. 12, No. 4 (Winter, 1962), pp. 217-234 Indiana University Press.

Stern, Tiffany. "Shakespeare the Balladmonger?" Rethinking Theatrical Documents in Shakespeare’s England. Ed. Tiffany Stern. London: The Arden Shakespeare, 2020. 216–238.

Another fabulous piece, Andrew. You make a totally persuasive argument for Dylan's direct descent from the line of bards and balladmongers that included Shakespeare. If you're ever in the mood for taking requests, I'd love to hear your thoughts on Dylan in relation to the rebel ballad tradition. In reading your latest, I sometimes found myself thinking of Lady Gregory's folk play The Rising of the Moon, in which an Irish fugitive flees the law in the disguise of a balladmonger, using ballads as code for his rebel activities. Could make for an interesting future installment in the series, if you're so inclined.

Thanks Andrew. What a fine exploration of the context and development of our favourite "song & dance man".