Opening Matters

References in brackets { } are to time point in the documentary The Volcano Named White . Quotes are used by kind permission of University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections Division (Uwdigital) Uploaded by University of Washington Special Collections on January 4, 2022. Presented by Robert (Bob) Schulman. Interviewer Bobby Farrell. Volcano Named White : King Broadcasting Company : Free Borrow & Streaming : Internet Archive

Lyrics quoted for study purposes are from Ballad of Donald White | The Official Bob Dylan Site Copyright © 1962 by Special Rider Music; renewed 1990 by Special Rider Music. There are minor deviations when sung, as you would expect, though only the official words are used below.

There are two versions of this song available to us, one from the McKenzie tapes (here) and the other from The Best of Broadside 1962-1988[i] (here)

Context and settling down to watch and listen

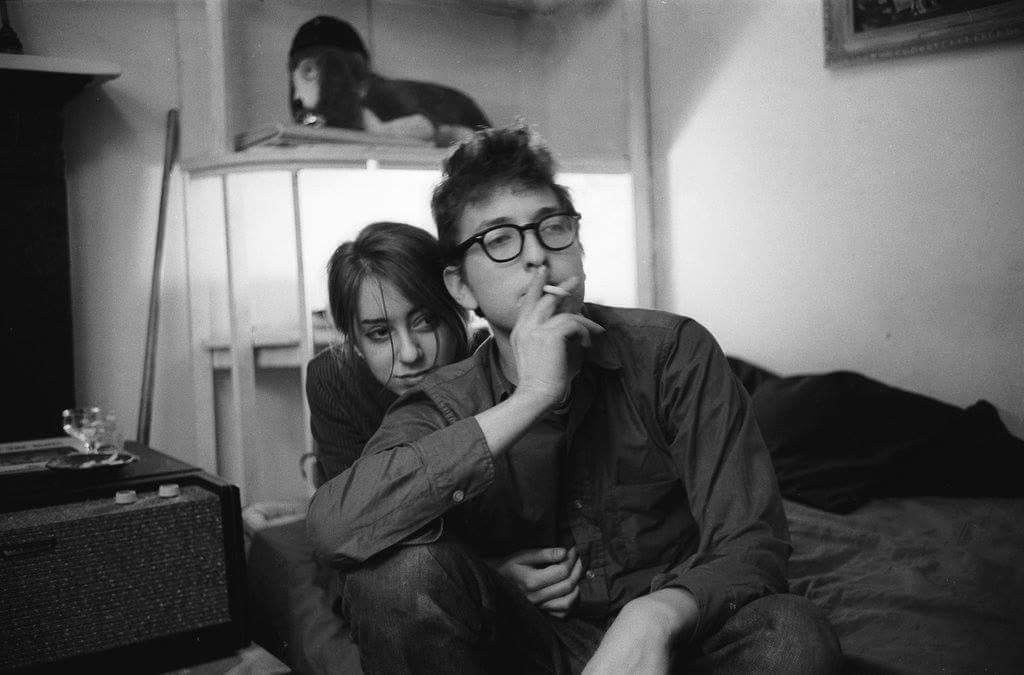

When Dylan moved on from protest songs to examine society at a deeper level, he declared that propaganda all is phony in the coruscating It’s Alright Ma, (I’m Only Bleeding). He included some of his own, earlier work in this denunciation, using the same word, “phony” to describe his “reasons and motives” when he wrote The Ballad Of Emmet Till. That , he said, “in all honesty was a bullshit song”[ii]. He mentioned, too, his tendency in those days to see something in the news and immediately write a song about it; The Ballad of Donald White came straight from watching a documentary on TV with Suze Rotolo. You can watch the same documentary and compare it to the song, as I do below.

It is natural for a creative, evolving artist to cast aside his previous work and persona and throw himself fully into the art he is currently creating. As audiences we can continue to enjoy the fruits of both. Dylan’s ‘finger-pointing’ songs contain much of worth, but it is also true that they range from juvenilia to masterly compositions. The Ballad of Donald White undoubtedly belongs to the former category, yet it is still instructive to view a young talent at work, shaping an instant response song, based on the news just heard and a melody from folk’s misty past.

The Ballad of Donald White is a prime example of a ‘journalistic song’. It was created almost, perhaps even partly, in real time, as and after Bob Dylan and Sue Rotolo watched the documentary “A Volcano Named White”.

Juvenilia it may be, but it offers you the opportunity to imagine yourself, back in the early Sixties, with Bob and Suze in their apartment in Greenwich Village watching this programme together and then following how Dylan created his song via the links at the beginning of this article.

The song draws heavily on themes of alienation, the external forces that shaped White’s criminality and institutionalization, mirroring key moments from the broadcast. Specific phrases in the song, such as White’s inability to connect with others, his comfort within institutions, and his eventual plea to return to them, closely mirror the sentiments expressed on TV.

Dylan tells us in the McKenzie tape where the melody originated: “I took this from Bonnie Dobson’s tune, Peter Emberley….” As Clinton Heylin[iii] has pointed out, he helps himself to some of the words as well as the melody which can be traced back to the Scottish Ballad Come All Ye Tramps And Hawkers. It is a popular tune, reckoned to stretch back in time from before John Calhoun put the words to Peter Emberley in 1881. It is also a melody to which Dylan would return to with masterly effect. [iv] Dylan takes the following lines from Peter Emberley:

There's danger on the ocean,

Where the waves roll mountains high

There's danger on the battlefield

Where the angry bullets fly

For his quatrain:

And there’s danger on the ocean

Where the salt sea waves split high

And there’s danger on the battlefield

Where the shells of bullets fly

Thus providing a rare flash of poetic language in the journalistic retelling of the tragic tale of Don White. Dylan also uses the old language of capital punishment and has a repeated phrase “Farewell unto” in place of Peter Emberley’s “Here's adieu unto” in his lyrics (though, when sung, Dylan uses the more modern “farewell to”).

Dylan’s phrases for the 20th Century capital punishment Donald White is to face, recall the earlier setting of the old ballad in a stream of references to hanging: ‘hanging tree’, ‘the gallows pole’, ‘the hangman’s knot’.

There are also pointed contrasts in the situation the narrators of each song. For example, where Don White tells us:

And I’m glad I’ve had no parents

To care for me or cry

For now they will never know

The horrible death I die

Peter Emberley bids an accusatory farewell to his father and a loving one to his mother. The ending for both, though, is inescapably the same in both songs, as it is in the TV Broadcast.

A sad, sad story

Both TV documentary and Dylan’s song tell ‘a sad, sad story’ of White’s early life, his alienation from normal society and his, preferred, life in institutions. They chronicle the inevitable consequences of the refusal of White’s pleas to be kept inside.

White starts out on his short life’s journey by entering the world of crime when he was still, in a phrase that occurs in both documentary and song, ‘very young’ .

Dylan picks up on the documentary’s The doctor added because he is a very bright boy, he seems worth saving, but there was no hospital equipped to handle him[v] and expands this into the first of many missed opportunities:

If I had some education

To give me a decent start

I might have been a doctor or

A master in the arts

However, Donald White's early life followed a very different path, than that of a 'decent start'. Instead, Dylan sings I used my hands for stealing / When I was very young to reflect Don’s own comment First in trouble with the law when I was 10. We are told White … spent all his life in and out of institutions and Dylan’s next song lines “And they locked me down in jailhouse cells / That’s how my life begun.” {02:20}

The cycle of his repeated run-ins with the law from a young age and of being in and out of institutions result in White feeling safer, less troubled and more at home when locked up in institutions, away from the chaos and pressures of outside life. While in ‘Peter Emberley “There's danger in the lumber woods, for death lurks sullen there/And I have fell a victim into that monstrous snare.” In Donald White’s life, and this ballad commemorating it, the snare is street life, outside the institution: “And for me the greatest danger/Was in society”.

Donald White tells us that: “I’d rather be institutionalized, as I was, it felt more like home…better than the outside world.” Dylan reflects White’s preference for prison over the outside world in the lines: “The inmates and the prisoners / I found they were my kind / And it was there inside the bars / I found my peace of mind.”

As far as the documentary is concerned, the peace White finds inside is only a relative one. Just as violence punctuated his life on the outside, we also hear of the same happening when White is inside. He is still tormented and mentally ill, after all, and ‘the volcano’ can and does still erupt. Near the end of the programme we are told: "Now he awaits his fate in the gaol in Seattle, where he has already tried to gouge out the eyes of a fellow prisoner.” {55:04-55:14 } Although the pressure, and concomitant release of any restraint, of being on death row may well have contributed to that latest explosion. Nonetheless, White is much calmer inside, and he, the authorities, the commentators and Dylan’s song are all agreed that he would be a danger if let out. Yet, that is precisely what happened.

Dylan’s song concentrates solely on the solace White finds in incarcerated existence. This is encapsulated in a telling and effective oxymoron: “So I asked them to send me back/To the institution home”. White felt secure there, it was indeed his ‘home’, and in a striking comment informs us that many inmates feel this way.

In life ‘outside’, White is a misfit, alienated and unable to communicate. Dylan’s song reflects the theme of alienation that pervades the documentary. White tells us that he “couldn’t talk to anybody, mother or father”, while Dylan sings ““I could never get along in life / With people that I met”.

Being all too aware of how he is “I’m broken as far as I can see” {38:55}, White is desperate to be kept inside. Dylan illuminates this desperation in White’s repeated requests to be returned to an institution through the vivid image of a penitent pleading to be returned to the penitentiary: “I got down on my knees and begged / ‘Oh, please put me away.’”

Although Dylan sings that this plea is ignored: But they would not listen to my plea/

Or nothing I would say , the greater tragedy is that White’s parole officer did listen and agreed this should happen but there was simply no room for him and consequently his despairing plea went unanswered.

“.. I was crying. And I don't usually cry for nobody. ..And I told him (parole officer, Wheeler) I say anywhere. Just lock me up, get off the street.” Officer Wheeler said he’d “do something for me” {39:00: 39:20} and he tried. However, we are told that; “Parole officer Arthur Wheeler tried to get Don White committed to a state hospital, but authorities said no. After that, officer Wheeler had 127 other paroled convicts to worry about.” {38:45 - 39-40}

No room, no time and the opportunity was lost. Dylan sings of this in the lines: But they said they were too crowded /For me they had no room and: “But the jails they were too crowded / Institutions overflowed / So they turned me loose to walk upon / Life’s hurried tangled road.”

White’s desire to return to institutional life being thwarted by overcrowded jails and institutions reminds us of the earlier lack of opportunity to ‘save’ the clever but mentally disturbed boy.

The remainder of Donald White’s short life is, from that moment, set on an inevitable course:

The jury found me guilty

And I won’t disagree

For I knew that it would happen

If I wasn’t put away

What White, and everyone else involved, ‘knew would happen’ ” took place on Christmas Eve, 1959.

Dylan reduces two murders to one by omitting the brutal killing, and it would appear rape, of the elderly woman in the laundry room. Schulman tells us that : “In this laundry room, Seattle's Yesler Terrace housing project, he savagely attacked and beat to death an old woman he never had set eyes on before. And asks: But was it only coincidence that this laundry room, where Don White killed was the same one used by his foster mother when he was killed?”

This murder and its attendant question are absent from the song which concentrates only on the killing of a man in an apartment block:

And so it was on Christmas Eve[vi]

In the year of ’59

It was on that night I killed a man

I did not try to hide

There is no doubt that Donald White committed the brutal killing. He does not deny it and far from hiding after the second murder, he sat across the road, having a drink and watching the police and ambulance services attend the scene. As there is no doubt over White’s guilt, so there is no doubt over his punishment. White bluntly tells us: “I’ve always thought I was going to end up on death row anyway. There’s no way I’d ever get away from that.” While Dylan puts the words predicting the death sentence more poetically: “I will die upon the gallows pole / When the moon is shining clear.”

The moral of this song

‘Now the moral of this story. The moral of this song’, is to learn from what happened; as the presenter of documentary Bob Schulman asked at the beginning “In presenting it, there is only one purpose in mind and that is to share with you what this tale can teach us about the urgent need for a better understanding of how criminals develop, the need for taking stock of the methods and institutions we have for reducing and for preventing crime and violence”. The documentary closes with the questions: “Is he an enemy of society or its victim? Has the course of his life been a waste or an inevitability? These are the burning questions that are hurled at us from the case of the volcano named White. Dylan echoes this in his closing verse with Donald White himself being the one to ask:

I’m wondering just how much

To you I really said

Concerning all the boys that come

Down a road like me

Are they enemies or victims

Of your society

Dylan converts the raw material of the probing documentary into a poetic version of White’s life, focusing on his feelings of alienation, his criminal past, and the peace he finds in prison as well as drawing us into the inexorability of his fate.

It is an early piece, first steps in the extraordinary journey Dylan was embarking upon and a mere six or so years later, and on the other side of a run of artistic triumphs unparalleled in American history, Dylan returned to the melody of Tramps and Hawkers/Peter Emberley for the song I Pity The Poor Immigrant.

Closing Matters

Some end notes for Bob cats.

I hope that you enjoy taking the opportunity to watch the documentary. When you do, I suspect that, like me, Dylan’s songs are so ingrained in you that you will hear familiar echoes: "I used to play in the cemetery"…"It's blowing like wind blowing in a pipe…""with blood in his eyes…" I even hear, “didn't know what it was for or what is was all about” in Dylan’s voice.

In the same way as we do not need Hattie Carroll’s ethnicity to be specified in The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll, so we do not need to be told that Donald White is a man of colour. The irony is there already, in reality, so there was no need for the writer to invent a poetic conceit.

The question at the end of the TV programme is posed amidst Don White singing “Parchman Farm Blues” a song by another ‘White’, this time Bukka. Bob Dylan covers Bukka’s Fixin' to Die Blues on his 1962 debut album.

POSTSCRIPT: Further info on the above

More on Donald White, with thanks to Ian Woodward, his archives and Todd Harvey’s The Formative Dylan.

All photos and links courtesy of Ian and I have to further thank him for reminding me of Todd Harvey’s The Formative Dylan book. I was merrily putting my article together imagining no-one had written about this song, How I could have forgotten to check Harvey’s book, which thrilled me as a resource when it first was published and has stood me in good stead many times since is a mystery.

Harvey discusses Dylan seeing Dobson perform Peter Emberley in February 1962 at Gerde’s Folk City. He also quotes Gil Turner , “I remember the first night he heard the tune he used for the ‘Ballad of Donald White.’ It was in Bonnie Dobson’s version of the ‘Ballad of Peter Amberley.’ He heard the tune, liked it, made a mental record of it and a few days later ‘Donald White’ was complete”

February 1962 ad for Bonnie Dobson at Gerde’s and here she is performing Peter A(E)mberley:

Bonnie Dobson - Peter Amberley - Live at folk city 1962

Soon afterwards, in the spring Broadside Reunion interview, Gil Turner quotes Dylan as follow :

“I’d seen Donald White’s name in a Seattle paper in about 1959. It said he was a killer. The next time I saw him was on a television set. My gal Sue said I’d be interested in him so we went and watched... . Donald White was sent home from prisons and institutions ’cause they had no room. He asked to be sent back ‘cause he couldn’t find no room in life. He murdered someone ’cause he couldn't find no room in life. Now they killed him ’cause he couldn’t find no room in life. They killed him and when they did I lost some of my room in life. When are some people gonna wake up and see that sometimes people aren’t really their enemies but their victims?”

Which in turn reminds me you can hear Bob introduce and play the songs, here, too:

Bob Dylan - Broadside Show And Sessions 1962-63

Harvey further informs us, via Antony Scaduto, that Sue Zuckerman, watched “A Volcano Named White” with Dylan and Rotolo on February 12, 1962. Zuckerman is quoted as saying: “Bobby just got up at one point and he went off in the corner and he started to write. He just started to write, while the show was still on, and the next thing I knew he had this song written, Donald White.”1 that Dylan wrote “The Ballad of Donald White” immediately following this television program.”

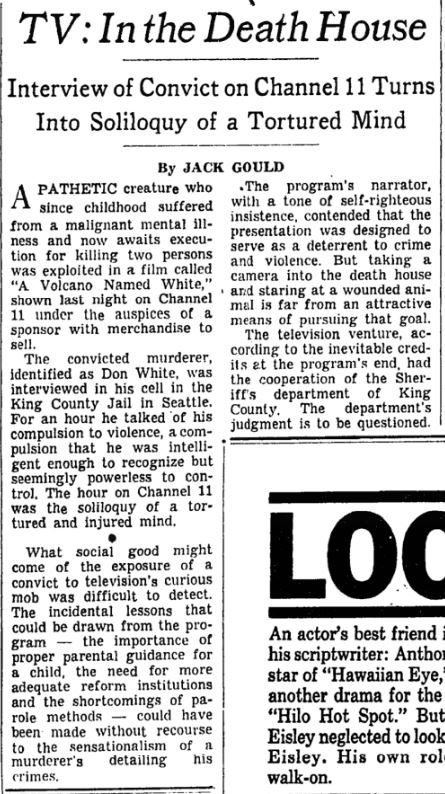

Below is an advert for the programme from The New York Daily News that day:

And here’s a review from the next day’s New York Times:

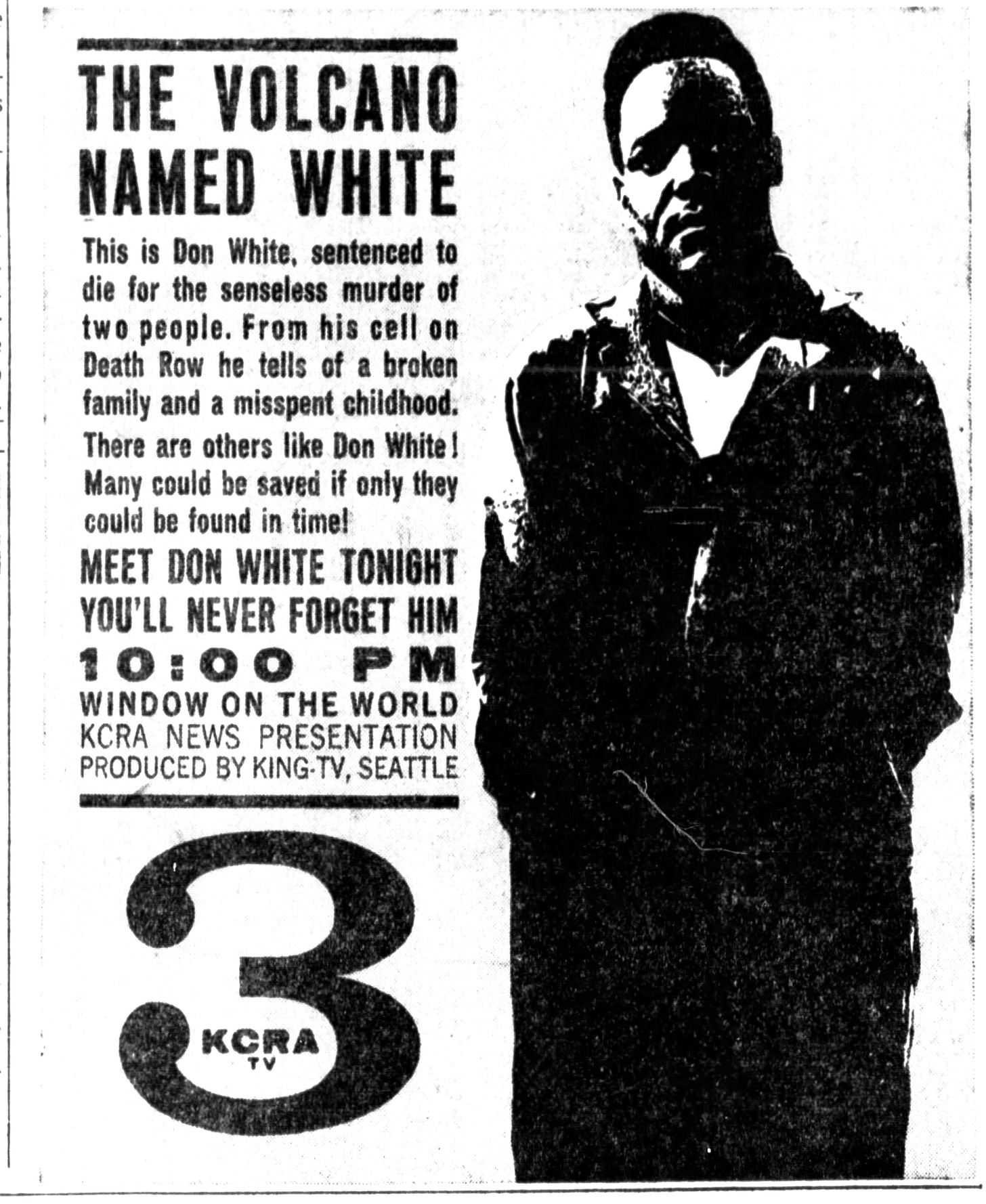

The San Francisco Examiner carried the following advertisement on March 27th:

[i] The Best of Broadside 1962-1988: Anthems of the American Underground from the Pages of Broadside Magazine ℗ Smithsonian Folkways Recordings

[ii] Clinton Heylin Behind The Shades Faber & Faber, 2001 pp 142

[iii] Clinton Heylin Behind The Shades Faber & Faber, 2001 pp 91

[iv] Original versions of Tramps and Hawkers written by [Traditional] | SecondHandSongs

[v] “He was only 14 when a psychiatrist said this boy shows evidence of a malignant mental illness. The outlook for eventual cure is not very hopeful, but treatment in an institution is absolutely necessary if he is not to end.” {04:20-04:30}.

[vi] Christmas time to me is rotten anyway…My mother told me that Christ was born in November or October and Christmas is heathen I came up like that, Christmas was wrong…I knew what Santa Claus was too quick.. {01:00-01:40}

Bob Dylan Antony Scaduto, Helter Skelter, London, 1996.